COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020 (WHO, 2020). This led to increased demands on healthcare services; significant changes were made within these services to manage the impact of prioritising pressures in the clinical setting, alongside adapting practices to meet service needs (Chidiac et al, 2020).

The pandemic's impact on primary care raised concerns, particularly for the 2-week cancer referral pathway. This was offset by increased emergency service demand alongside emerging evidence of delayed cancer diagnosis with related mortality (Flynn et al, 2020; Maringe et al, 2020). Predictions were made, highlighting the potential increased impact on palliative care services, as changes on survival and prognosis rates became evident with reduced treatment options and in some dire cases, no longer an option (Maringe et al, 2020).

At the start of the pandemic, specialist community palliative care services shifted from a predominately face-to-face led service. Adaptations included the incorporaton of technology-led consultation and virtual ward rounds to support service delivery and reduce the risk of infection (Powell and Siveria, 2020).

Background

The challenge of meeting palliative care demands resulting from the pandemic reflected known workforce shortages, and the need for an improvement in collaborative working in community services (The Kings Fund, 2018; The Kings Fund, 2019). Suggestions to manage demand had predominately encouraged inter-professional working and more support to generalist services from specialist palliative care (SPC) services (Finlay, 2009; Rowlands et al, 2012), but without an agreed model of delivery (Etkind et al, 2017; NHS England, 2019; The Kings Fund, 2019). It was recognised that SPC services would have to adapt to meet the high demand for their services (Etkind 2019; Kamal et al, 2019).

Adapting to the new way of working increased pressure on the local clinical nurse specialist (CNS) palliative care services, which had already experienced a 52% increase in service requirement over the past 5 years, with further anticipated challenges regarding the implimentation of the NHS's Long Term Plan (2019). Swift changes had to be implemented within the CNS service to cope with the real and anticipated demand for care. This included the creation of a coordination hub for managing palliative and end-of-life care patients, as well as an increased level of collaboration with other local healthcare teams. It brought forward the thinking that having both the nursing and allied health professionals working alongside each other as a team would increase capacity and improve resilience. In addition, a virtual ward (Ferry et al, 2021) was created, which enabled healthcare professionals to attend to personal care duties and nursing needs.

Consultation with patients in primary and community care services has historically been face-to-face. However, telephone/video consultation became an option during the pandemic, when appropriate, in order to provide services while managing risk (General Medical Council (GMC), 2020; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2020; Royal College of Nursing (RCN), 2020). Telemedicine was introduced by the CNS team to support changes in practice and has resulted in many positive outcomes (Perrin, 2020).

Aim of study

The aim was to understand the experiences of the CNS team following implementation of new working practices during the pandemic.

Method

Design

A phenomenological approach, as defined by Bryman (2016), was used to inform the study's design, and semi-structured interviews were used to obtain detailed accounts from individuals about their experiences.

Participants and data collection

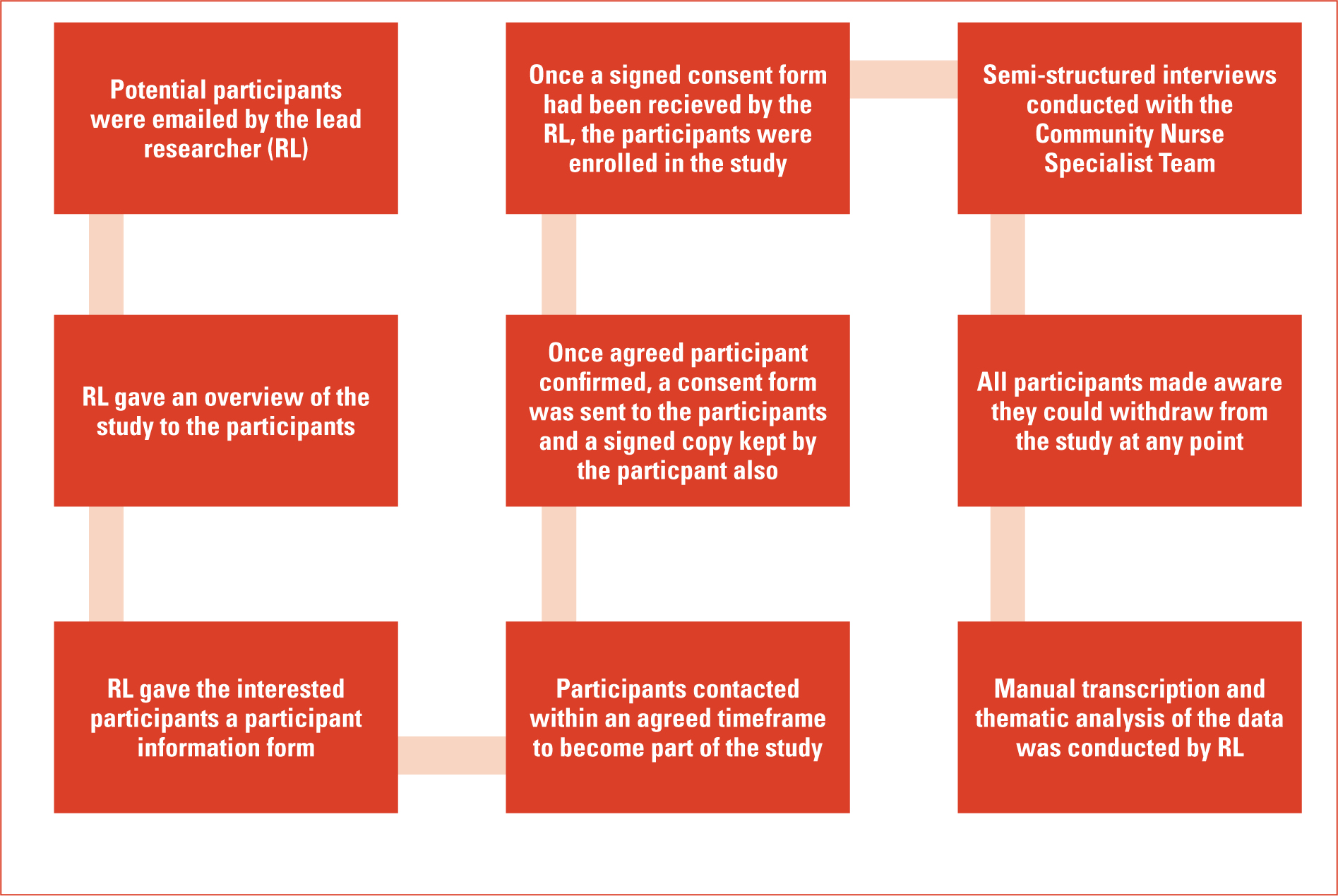

Following ethical approval, a purposive sample of 12 CNSs were recruited; of the 11 who participated, one declined due to staff illness (Figure 1). Semi-structured interviews were conducted via Microsoft Teams (MS Teams) using a schedule of 9 questions reflecting the study objectives (Table1). The nursing and CNS experiences of participants varied widely, with nursing experience ranging from 6 to 32 years and CNS experience from 2 to 16 years. Data collection took place between June and August 2021; all interviews were conducted by the lead researcher.

Table 1. Interview schedule

| No. | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | Can you tell me your experience of working through the pandemic? |

| 2 | What changes in your working environment were implemented as a pandemic response? |

| 3 | What changes do you think relating to your working practice may have had a positive influence on patient care? |

| 4 | What changes from your perspective have had a positive influence on support to partners (health and social care) also providing healthcare? |

| 5 | What changes have you observed that may not have had a positive effect? |

| 6 | How do you think the use of technology has influenced patient care and support to partners? What was good? What was not good? |

| 7 | What is your experience of team collaboration throughout the pandemic response? |

| 8 | What support mechanisms that were available did you use to help maintain your resilience during this time? |

| 9 | Is there anything else you can add to describe your experience working in the team throughout the pandemic response? |

Data analysis

Data were analysed using the framework developed by the National Centre for Social Research (Ritchie and Lewis, 2003). All interviews were transcribed verbatim and returned to the participant to confirm that it was an accurate record of the interview. Minor revisions were made as requested. The transcripts were separately, coded manually and an agreed thematic framework was established, revisiting the study aims and objectives.

Ethical considerations

The study received ethical approval from a local research ethics committee. The researchers ensured they upheld the domains of the Research Governance Framework (Health Research Authority, 2021) and adhered to the principles of the General Data Protection Regulation (2018).

Results

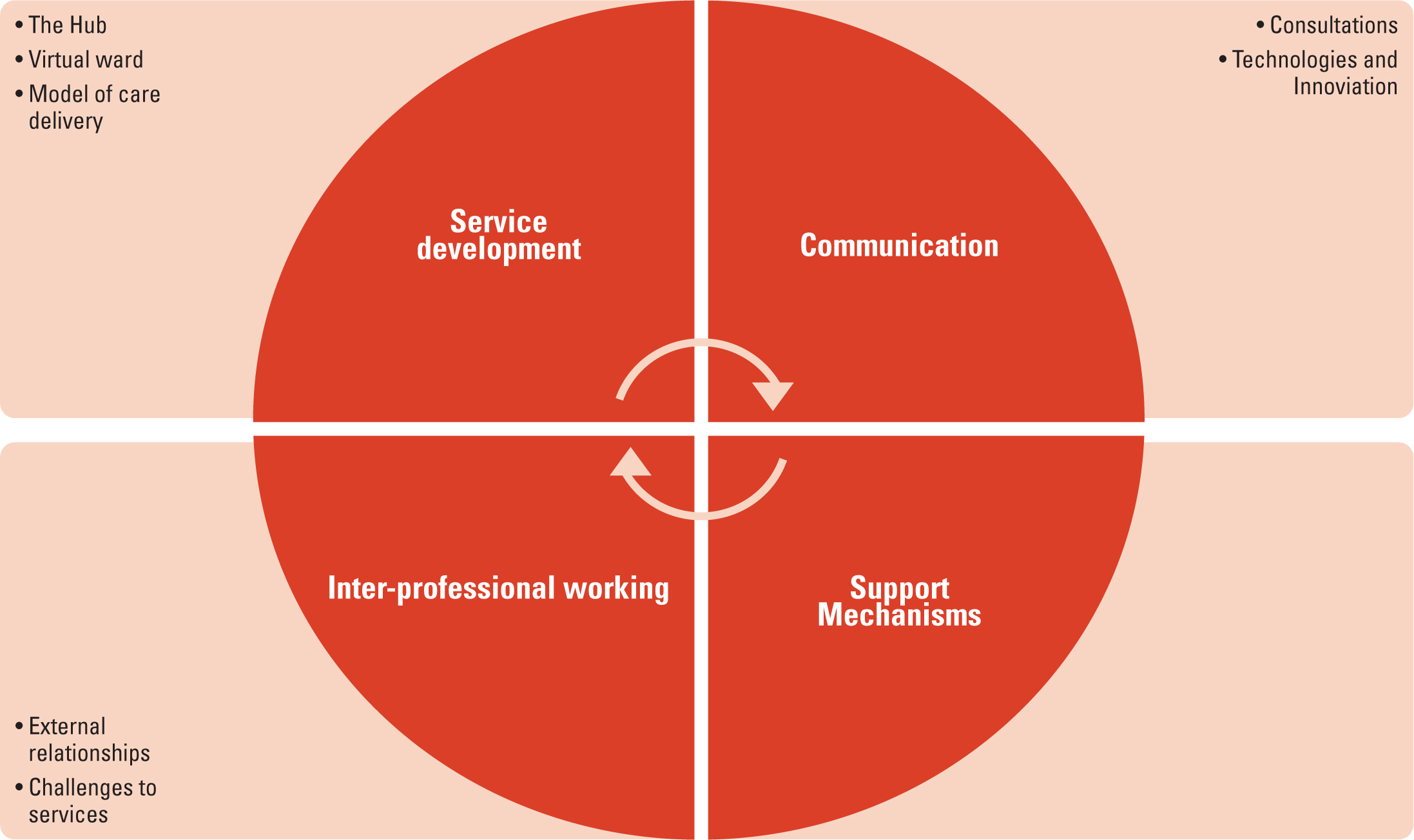

Four main themes emerged:

- Service development

- Communication

- Inter–professional working

- Support mechanisms.

Service development

Service development relates to the rapid changes implemented to the community team as part of the pandemic response. Many participants described the impact of the changes which included both positive and challenging elements. Sub-themes became evident and have been listed below.

The hub

The creation of the coordination hub was mentioned positively and consistently by all participants. The hub provided a coordination centre for local end-of-life care, and included a logistics service and became a central point of contact for all services providing a lead in the collaboration of services.

‘We had had the vision for the hub for 2 years and it was pulled together in 5 days. We were moved in a direction of setting up something quite spectacular.’

(Participant 2)

‘The hub logistics was also set up using volunteers… they were able to go out and deliver medications, take out equipment and support the team.’

(Participant 6)

‘Multidisciplinary working had a positive influence on patient care because we were working alongside each other in the hub; we had a much greater appreciation of each other's roles and workloads.’

(Participant 4)

Virtual ward

The virtual ward was integral to the hub and end-of-life care provision. The aim was to enhance holistic care, providing nursing and personal care to patients within their home either by a nurse or a healthcare assistant. It also supported the activity of the local district nursing teams and hospital discharges to the community, which enabled people to die at home rather than be admitted to hospital or a hospice. The participants commented:

‘Nurses and healthcare assistants worked together and a lot of the visits were allocated to the virtual ward. By working alongside the Community Healthcare Assistant (CHCA), the CNS could administer medications before care and also offer support to the family.’

(Participant 3)

The virtual ward raised awareness of hospice services and the challenges in providing such services:

‘The virtual ward raised the awareness of what we (CNS) were able to do. I think other healthcare professionals such as district nurses (DNs), GPs now acknowledge much more of what we can deliver in terms of our skill sets and understand we can offer more specialist palliative care needs.’

(Participant 9)

Model of care delivery

Care delivery changed from CNS case load management, with planned visits and contacts with support of a 24–hour helpline for reactive needs. The model was described by the participants as having advantages and disadvantages:

‘Working from a reactive model and focusing on having the right nurse, in the right place at the right time is more effective than working from a case load and means the right “team” is allocated, which often extends to the DN/react teams.’

(Participant 8)

‘I think we were having to address a lot of conversations relating to advance care planning, we could be the first service to visit and address this; difficult conversations and implementing interventions rapidly was challenging at times.’

(Participant 7)

Communication

Communicating is always challenging and this theme explored factors considered by the CNS when communicating with patients, including consultations underpinned through technology and innovation. There were two sub-themes identified:

Consultations

The CNS team adapted from a predominately face-to-face service to primarily telephone/video consultations with face-to-face visits triaged following risk assessment. Home visits were agreed in advance with patients, as many were shielding. Participants suggested:

‘We are much more skilled in assessment by telephone and video links now, you have to rely on honed assessment skills to ensure you have extrapolated all the information to inform the management plan.’

(Participant 9)

‘A benefit of using video assessment was other family members and other services such as GPs could join the consultation regardless of where the patient lived geographically. It enabled first hand communication.’

(Participant 1)

Some described how patients and their families were worried about home visits:

‘What I found was some people did not want to have a CNS visit their homes and would ask for telephone assessment.’

(Participant 1)

‘People were scared of having people in their home environment, so using telephone and video consultations met their needs.’

(Participant 3)

Another suggested the use of technology was challenging in some circumstances:

‘Video technology was not always easy for our elderly patients. It was very good when it worked but it did cause anxieties for some patients.’

(Participant 5)

Technology and innovation

The use of technology and examples of innovation were raised by participants. The hub was coordinated using a dedicated hub document supporting all aspects of coordinated service delivery and using MS Teams. Some suggested:

‘Our hub doc had started as a basic document then became a live and interactive interface that showed calls in/out/waiting together with visits allocated to all multidisciplinary teams (MDT) including the virtual ward.’

(Participant 11)

‘Using Teams has transformed our ways of working. We use it to have a daily coordination meeting at 9:15am, which supports the work for the day and brings everyone together as a team.’

(Participant 4)

‘Training has been able to continue through utilising MS Teams as the method of delivery and allowed for continual staff development.’

(Participant 9)

Inter-professional working

The pandemic response demanded collaboration to ensure that the most appropriate service delivered patient care and that staffing challenges were shared.

External relationships

Participants suggested relationships with other services, particularly the DN team, were stronger as a result of greater collaborative working, which also reflected greater understanding of roles:

‘Before the pandemic, we worked in silos with each service delivering independently; working more collaboratively has ensured we do not duplicate work; we took on additional tasks such as fast–track that were previously completed by the DNs. This improved the delivery of care with one visit rather than multiple visits.’

(Participant 1)

‘Our relationships with the DN teams have really improved. We understand their role more and they do ours.’

(Participant 6)

It was evident that everyone used peer support from an organisational perspective and from the wider community team.

‘We always supported each other, working collaboratively with internal teams, making sure people isolating or shielding were always included, we pulled together and in a weird way within a difficult time and it has been a positive experience.’

(Participant 10)

Challenges to services

Challenges included the sense that other services were not as accessible compared to pre-pandemic, such that participants reflected on needing to, on occasion, call on skills not utilised for some time, or having to develop new ones. They suggested;

‘I felt we were impacted by changes to other primary services and it felt overwhelming at times, we never say it's not our problem–we will make a plan together and work to solve any problems or concerns.’

(Participant 6)

‘Often when I visited a patient I was the first to see them for months, they were often at advanced stages of illness-had no support of oncology services. I felt my clinical skills had to be sharp, using my assessment skills in ways I had not been called upon to do before.’

(Participant 5)

Support mechanisms

This theme explored the mechanisms that supported participants as they worked through the pandemic. Participants spoke about the emotional impact of the work with fears for patients, colleagues, their families and themselves with increased responsibility towards patient care when resources were significantly stretched:

‘It was scary, the awareness that it would affect my work, potentially myself and family, colleagues, we were all scared as healthcare professionals as we were more exposed from our working environment as we remained patient facing.’

(Participant 1)

‘The overall impact affected every aspect of our lives, professionally and personally, affecting family relationships due to isolating and schooling for our children. We all had personal fear and anxiety of the threat of testing positive and the potential impact this would have on patient care.’

(Participant 4)

Another reflected on the impact COVID had as a knock-on effect to patient care:

‘For me personally, what I have found the most difficult was patients who could have had earlier treatment intervention, but did not get access to it and therefore deteriorated more quickly.’

(Participant 9)

Several mechanisms were used to help maintain resilience including personal, peer and community support. Fears experienced by the team were balanced by the support from multiple agencies.

‘The whole team has been very supportive of each other–from consultants, team leaders and other colleagues. We used each other to debrief; I didn't feel there was a hierarchy and I was confident to ask for support from any team member.’

(Participant 3)

Another comment related to the reduction in social interaction resulting from new working practices:

‘Social interaction was reduced as we had to change the way we worked. We had to maintain a 2–metre distance from one another, you could not physically support a distressed colleague.’

(Participant 1)

Others recognised the need to have personal time to help maintain resilience:

‘With so much happening, the temptation to log in and read emails on your days to keep up to date was tempting. However, you had to stop and take time away from work to look after yourself, taking time with family and being outdoors helped me.’

(Participant 6)

Discussion

COVID-19 had a challenging impact on healthcare services. A coordinated approach was developed to support such an increasing demand in an SPC setting (Bone et al, 2018; Hewison et al, 2021). There were no defined frameworks for the community palliative care provision within a pandemic/epidemic (Etkind et al, 2020; Mitchell et al, 2020). However, collaborative models were advocated, which enabled community palliative care services to develop and provide the necessary support to patients. End-of-life care in the community is often provided by different organisations, such as DN teams and hospice-specialist CNS teams (Boole and Watson, 2021). In response to pandemic–related increased palliative care needs, a community coordination hub was developed, reflecting the requirements and aspirations of the NHS Long Term Plan (2019) and the Kings Fund Community Plan (2019). These plans suggest that without service collaboration, demand for future palliative care needs would be difficult to meet. While one of the most challenging objectives for healthcare is to reduce inappropriate hospital admissions, the need for complex patient management in primary care has received less policy attention, both globally as well as in the UK (Park et al, 2020). The pandemic forced the discussion to drive services forward collaboratively and the CNS team supported the need for coordination of services, which was brought forward because of the pandemic. Locally, a coordination hub model based on the concept of a ‘virtual ward’ was developed, which contributed significantly towards optimising patient care (Lewis et al, 2011). The virtual ward model was chosen, as previous research has shown it can reduce hospital admissions and offer the clinical support of a hospital environment within the patient's home, as teams work together to meet the patient's needs (NHS, 2021; Schultz, 2021).

Throughout the pandemic, the CNS team used the concept of the virtual ward by offering SPC reviews to optimise symptom management, enabling the person to remain at home. This was endorsed by patients, as they wanted to avoid hospital admission or other care settings due to fears of contracting COVID-19 and restrictions on visitors (RCN, 2021). Moreover, participants reported that ‘many patients did not ring because they did not want to let anyone into their home and only called when they had reached a crisis point’. This was also reported by DN teams who felt patients were reluctant to allow home visiting for regular review (RCN, 2021). This often resulted in patient's symptoms or social needs presenting as crisis due to infrequent monitoring (Smyrnakis et al, 2021), as confirmed by the participants of this study. Participants also noted that some patients were reluctant to present to healthcare professionals. As predicted by Maringe et al (2020), in some instances, this led to delayed diagnosis and presentation of advanced incurable disease and cancer deaths.

Palliative care provision often enables complex and challenging decision making (Etkind et al, 2020) and the needs for patients was mentioned by several participants as challenging, particularly, the need to ensure that advance care plans (ACP) were in place (NICE, 2019). The findings from this study reflect a study of Denmark GPs who recognised the need for ACPs, but also encountered the more difficult situation of having to approach it without the grounding of an established relationship where the conversations had been built over time (Dujardin et al, 2021). However, while the recognition to facilitate ACP in a time of uncertainty was encouraged, caution was communicated by NHS England and a joint statement from the General Medical Council and Nursing and Midwifery Council (GMC and NMC) (NHS England, 2020; GMC and NMC, 2020) advising that ACPs should remain individual and person-centred.

Although the pandemic was challenging at times, the participants reported improved working relationships with the wider teams, especially DN teams. Working collaboratively can have challenges; however, the participants felt that enhanced relationships were achieved by the creation of the coordination hub which triaged and coordinated patients' needs, ensuring the right service attended. This brought about a more coordinated response and understanding of each other's roles and responsibilities.

Primary care services changed during the pandemic, resulting in increased calls to CNS services. A study by Mitchell et al (2021) supported this finding; GPs reported undertaking 40% fewer face-to-face visits relating to end-of-life care. However, participants suggested that the coordination hub and virtual ward raised the profile of the team positively with both the GPs and DNs.

Despite the challenges of continuing patient services during the pandemic, participants described how maintaining resilience was vital for them and how important it was for them to take care of themselves. They described how ‘ensuring time taken to go for walks, enjoying hobbies and time away from work’ helped to maintain their resilience as advocated by Duncan and Smart (2021). The CNS team employed emotional regulation naturally as a response and appeared self–aware and proactive in managing this. However, this should not lead to complacency as the challenge is to sustain resilience and the momentum of self–care (Bennett et al, 2020). Team support was also a significant component in maintaining resilience for them with several opportunities to debrief and share experiences described as important by Donnelly et al (2021) and Villar et al (2021), which contributes to shared international experiences. It was noted in the participant responses that ‘team’ was not isolated to immediate, internal teams, but the wider nursing teams, including DN colleagues.

Within this study, staff working in leadership roles were described as supportive and some suggested that hierarchy was not a barrier and that they felt confident about accessing support, if needed. Another form of support appreciated by the CNS team was being valued and appreciated through donations from the public and businesses which included food and practical gifts. Studies from China and the UK found similar assistance and value from this line of support (Liu et al, 2020; Vindrola-Padros et al, 2020). Understanding the workforce pressures and demands is essential to ensure provision of support needed to maintain resilience and wellbeing.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic required innovative ways of working to be introduced. A community CNS palliative care team introduced a virtual hub and a virtual ward, allowing for a collaborative, coordinated partnership to providing patient care. Improved team work and understanding different community roles was seen as a positive by participants. The CNS workload reportedly increased due to changes in primary care service provision. The use of technology to communicate with patients and colleagues was seen as imperative to the success of care delivery. Resilience was maintained by the wider team support and debrief sessions. The model of collaborative working, including the coordination hub and virtual ward has been embedded to practice and the use of technology and innovation continue to be implemented.

Key points

- The use of technology, including video consultation, virtual platforms for communication, both inter-professionally and patient facing, were embraced and positively adapted into working practice

- The creation of the coordination hub enhanced patient care and inter-professional working

- The positive outcome of enhanced inter-professional working between the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) and district nursing teams allowed the model to move away from working in ‘silos’, which benefited patient need and service

- The impact of the pandemic increased the demand for palliative care services particularly to the 24-hour telephone support line.

CPD reflective questions

- How can specialist palliative care (SPC) services further support generalist services in the delivery of palliative care ?

- How can inter-professional working relationships between organisations be facilitated and improved?

- What are the benefits and challenges for using video technology for patient consultation?