Nasogastric tube (NGT) placement is common for community-dwelling adults who are unable to meet their nutritional requirements orally. The nasogastric tube provides access to the stomach and is indicated for therapeutic purposes, including feeding and medication administration. Although blind insertion of NGTs with initial placement confirmed by the nurse is considered to be safe, incorrect positioning can have serious or fatal consequences (National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA), 2016).

Various methods have been suggested to verify NGT placement, including pH analysis (Holmes, 2012; Boeykens et al, 2014); auscultation test (Simons and Abdallah, 2012); capnography or capnometry (Chau et al, 2011; Miller, 2011); and chest X-ray (Taylor, 2013). A pH value of 1–5.5 for the aspirate is considered in the safe range, and this can be used as the first-line reference to exclude NGT misplacement in the respiratory tract (NPSA, 2011). However, studies have found false-negative pH findings among patients who received acid-reducing medications (Kim et al, 2012; Boeykens et al, 2014). Although the auscultation test allows good assessment of tube placement, it is not reliable in identifying a malposition of the NGT (NHS Improvement, 2016; Anderson, 2019). A few studies have reported that capnography or capnometry helps to confirm NGT placement, but a capnogram alone may not truly reflect tube position and an X-ray is unavoidable (Chau et al, 2011; Ryu et al, 2016). While all these tests have limitations in NGT placement verification, chest X-ray remains the gold standard for NGT placement confirmation (NPSA, 2016).

To promote safe practice, clinical guidance on verifying the correct position of NGT has been produced for community nurses (NHS Improvement, 2016; National Nutrition Nurses Group (NNNG), 2019), and, at present, pH analysis is the only first-line reference standard. When the aspirate pH is ≤5.5, the NGT is confirmed to be safely placed in the stomach. However, when it exceeds 5.5 or no gastric aspirate is obtained, a chest X-ray is recommended and has been considered as the second-line reference standard. The auscultation test and clinical judgement on the gross appearance of the aspirate are not recommended as standalone methods but supplementary references.

It is not rare for community nurses to get failed verification of NGT placement, since the pH test is limited by its lower sensitivity (Taylor et al, 2014), while auscultation ‘whoosh test’ lacks specificity (Boeykens et al, 2014). Moreover, transport of bedbound patients from community settings to the hospital for an X-ray scan poses a problem. The long waiting times at the emergency department also interfere with feeding, hydration and medical regimens, besides the patient being subjected to avoidable irradiation (Chan et al, 2012). As such, it is worth exploring other point-of-care tests with high accuracy for verifying correct NGT placement in a setting where X-ray scans are not readily available.

In recent years, studies have reported that point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) provides good diagnostic accuracy and helps confirm NGT placement (Chenaitia et al, 2012; Kim et al, 2012; Brun et al, 2014; Tai et al, 2016). However, to date, there are no studies conducted on the feasibility of using this in community nursing. Having considered the practicability and limitation of conventional tests, a study was designed to investigate the effectiveness of POCUS and to explore the feasibility of incorporating this imaging modality into first-line reference standards for NGT placement verification.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective study was performed in a convenience sample of patients who underwent NGT insertion conducted by community nurses of Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital (PYNEH), Hong Kong, between March 2018 and November 2019. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Hong Kong East Cluster (HKECREC-2019-102) and the Hospital Authority of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region in accordance with requirements under standard operating procedure and the Declaration of Helsinki on reviewing and publishing information from patients' records. Informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study and because management of patients would not be affected.

Participants

A total of 68 NGT placement verifications were examined retrospectively. Eligible patients were those over 18 years of age who required an NGT insertion by community nurses with additional POCUS performed by trained nurses between March 2018 and November 2019. No cases were excluded.

Data collection

The medical records of patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were traced and reviewed from the clinical management system (CMS) and community-based nursing information system (CBNS). Demographics, past medical histories, clinical parameters, acid-reducing medication prescription, nursing treatment and emergency department admission histories for X-ray control immediately after NGT insertion by community nurses were identified. Documentation on the results of assessment tests after NGT insertion, including ultrasonography, pH test of gastric aspirates and X-ray scans was collected.

Study protocol

To ensure that the blinding process was appropriately executed and to limit inter-observer variability in the POCUS technique, a single blinded approach was used and only two trained nurses carried out the ultrasonography test. First, all NGTs were inserted by a community nurse per usual practice. The nose-ear-xiphoid (NEX) method was used to measure the length of insertion, and the NGTs were of size 14 or 16 Fr. The tube was lubricated at the first 5–7.5 cm of the tip with water-soluble lubricant and gently advanced by directing it along the floor of the nasal passage and downward toward the tip of the ear to avoid traumatising the turbinate until it reached the measured length. The nurse proceeded to verify placement using the aspirate pH test. The placement of the NGT in the stomach was confirmed if the pH was ≤5.5 according to clinical guidance.

After securing the tube to the patient's nose and cheek with adhesive tape, the nurse then contacted the trained operator to perform POCUS prior to any use of the tube. The nurse who inserted the NGT would receive a phone call from the operator once the POCUS was completed. Transportation would be arranged for the patient for radiographic examination in hospital only if the gastric aspirate pH was >5.5 or feeding would be resumed. The community nurse was blinded to the results of the POCUS to ensure that the result would not affect the usual management of patient care.

Additional POCUS was performed only when a trained operator was available on a weekly basis, though the days were not fixed. The operator was blinded to the pH findings and performed the ultrasonography within 30 minutes after NGT placement. Both trained nurses who performed the POCUS were experienced and certified in emergency ultrasound, through a one-day, 8-hour training workshop dedicated to study the specificities of this type of ultrasound examination. The scanning technique was assessed and evaluated by a qualified trainer during the practical session. Furthermore, trainees were required to obtain a minimum of ten positive scans in line with the data collection process while the scanning technique was assessed.

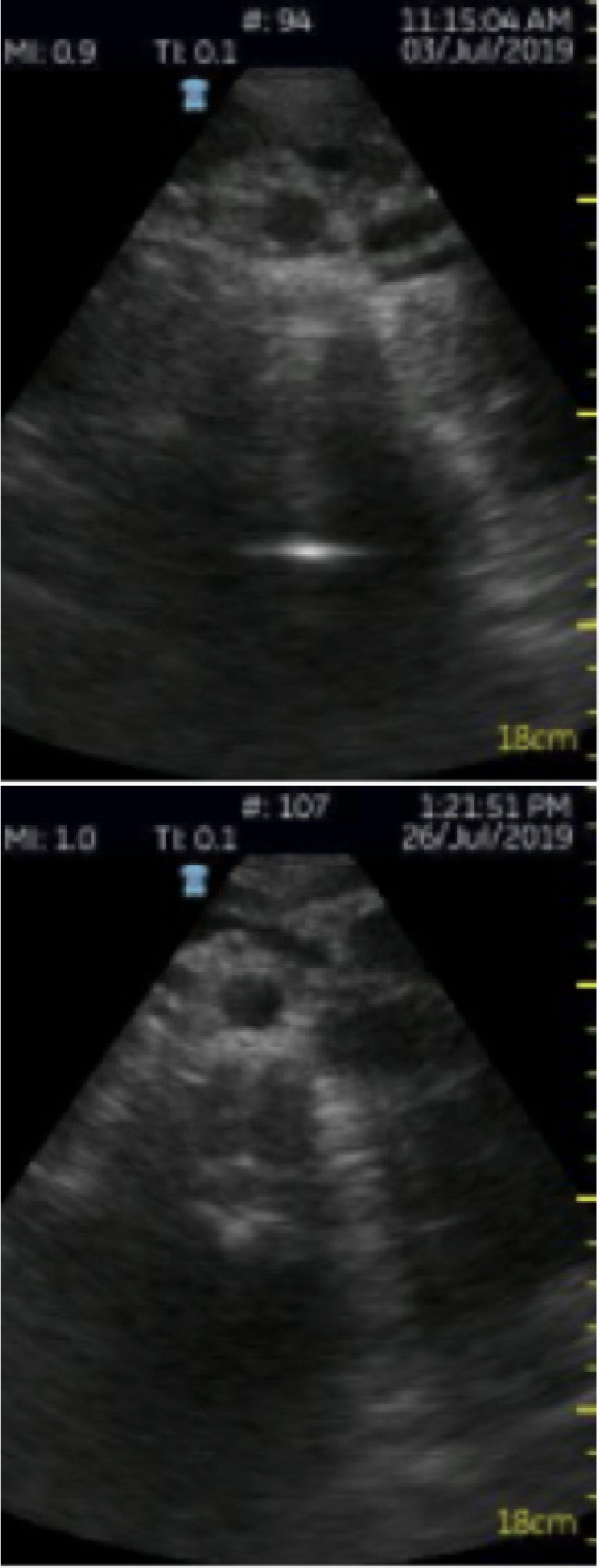

A portable ultrasound system (Vscan; General Electric Healthcare) with dual probes was used: linear array transducer (3.4–8.0 MHz) and phased array transducer (1.7–3.8 MHz) for neck and subxiphoid scanning, respectively. The technique used by the nurse operators was standardised: the linear probe was placed transversely on the anterior neck just superior to the suprasternal notch, fanning it to the left at the level of the thyroid gland and focused on the oesophagus with transversal viewing. Once the oesophagus was focused, the probe was spun for longitudinal viewing. Along with applying the phased probe with transversal viewing in the subxiphoid region, the left lobe of the liver was used as an internal landmark and the transducer was tilted toward the left subcostal area until the stomach was imaged. The neck ultrasonography examination was considered as positive when the acoustic shadow of the NGT was visualised in the oesophagus, appearing as a hyperechogenic circle in transversal viewing and a hyperechogenic line in longitudinal viewing (Figure 1). For positive subxiphoid scanning, the tube image appeared as a hyperechogenic line in the stomach. When the acoustic shadow of a NGT was not seen in the stomach, 50 cc of air was injected through the NGT, and it was considered well placed if the ultrasonography showed dynamic fogging (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Neck ultrasound with the nasogastric tube seen in the oesophagus (arrow: acoustic shadow of tube). Top: transverse scan. Bottom: longitudinal scan

Figure 1. Neck ultrasound with the nasogastric tube seen in the oesophagus (arrow: acoustic shadow of tube). Top: transverse scan. Bottom: longitudinal scan  Figure 2. Subxiphoid ultrasound. Top: nasogastric tube appears as a hyperechogenic line in the stomach. Bottom: hyperechogenic fogging in the stomach

Figure 2. Subxiphoid ultrasound. Top: nasogastric tube appears as a hyperechogenic line in the stomach. Bottom: hyperechogenic fogging in the stomach

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23. For descriptive statistics, both mean and standard deviations were used to summarise continuous variables, while nominal variables were reported in terms of percentage. Inferential statistics including the calculation of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values (PPVs) and negative predictive values (NPVs) was used to assess the diagnostic ability of the interventions.

Results

A total of 68 patients were included in the study, with a male:female ratio of 24:44 and a mean age of 82.13±9.43 years. Some 63 (92.65%) patients underwent scheduled NGT replacement, while five (7.35%) required ad-hoc replacement due to dislodgement or blockage. For patients with correct tube placement, 47 (71.21%) had histories of emergency admissions for X-ray verification: 44 (66.67%) needed X-ray controls due to false negative pH analysis from acid-reducing medications, and no gastric aspirates were obtained in the remaining three (4.55%) patients. Some 64 (94.12%) had underlying morbidities, and cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) accounted for the largest share among these, followed by dementia and malignancy (Table 1). Some 67 (98.53%) patients had a clinical frailty scale (CFS) score of ≥7, and 26 (38.24%) of these individuals died within 18 months of the study.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the patients

| Demographics | Total (n=68) | Correct placement (n=66) | Incorrect placement (n=2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (59–100) | |||

| Mean | 82.13 | 82.02 | 86 |

| SD | 9.43 | 9.47 | 2 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 24 (35.29%) | 23 (34.85%) | 1 (50.00%) |

| Female | 44 (64.71%) | 43 (65.15%) | 1 (50.00%) |

| Use of acid-reducing medications | |||

| H2 antagonists | 6 (8.82%) | 5 (7.58%) | 1 (50.00%) |

| Proton-pump inhibitors | 55 (80.88%) | 55 (83.33%) | 0 (0%) |

| Clinical Frailty Scale score≥7 | 67 (98.53%) | 65 (98.48%) | 2 (100%) |

| Mortality | |||

| 6-month | 18 (26.47%) | 18 (27.27%) | 0 (0%) |

| 12-month | 2 (2.94%) | 2 (3.03%) | 0 (0%) |

| 18-month | 6 (8.82%) | 6 (9.09%) | 0 (0%) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cerebrovascular accident | 46 (67.65%) | 46 (69.70%) | 0 (0%) |

| Congestive heart failure | 5 (7.35%) | 5 (7.58%) | 0 (0%) |

| Dementia | 29 (42.65%) | 27 (40.91%) | 2 (100%) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 7 (10.29%) | 7 (10.61%) | 0 (0%) |

| Malignancy | 11 (16.18%) | 11 (16.67%) | 0 (0%) |

| Parkinson's disease | 10 (14.71%) | 10 (15.15%) | 0 (0%) |

| Past history of X-ray verification | |||

| Negative pH analysis | 46 (67.65%) | 44 (66.67%) | 2 (100%) |

| Gastric aspirate could not be obtained | 5 (7.35%) | 3 (4.55%) | 2 (100%) |

SD=standard deviation

The average duration of POCUS for verifying NGT placement was 26±3 seconds (median=27 seconds). There were no cases of NGT misplacement in the respiratory tract in any of the patients, and ultrasonography visualised the NGT in the neck area in 63 (92.65%) patients. Excess mobilisation in one patient, excess contracture in three patients and malignancy in one patient led to failed visualisation, although the NGT had been placed in the oesophagus. In the subxiphoid area, ultrasonography visualised the NGT in 61 (89.71%) patients. Due to gas interposition, it failed to visualise the NGT in five (7.35%) patients in whom the NGT was correctly placed in the stomach as verified by the pH and/or X-ray reference test (sensitivity=92.42% (95% CI: 83.20%–97.49%). While the tubes were not visualised in these five patients, correct gastric placement was inferred on the basis of fogging observed in two of the five patients (sensitivity=95.45% (95% CI: 87.29%–99.05%). Further, the results in the remaining two (2.94%) patients in whom the NGT could not be visualised in the subxiphoid area were compatible with both pH and X-ray findings: the tube was located above the diaphragm in these patients because of the existence of a large hiatus hernia. The results indicated that POCUS had a specificity of 100%. Its positive and negative predictive values were 100% and 40%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Diagnostic accuracy of POCUS in confirming NGT placement

| POCUS test | Reference test (pH or X-ray) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct position (n=66) | Incorrect position (n=2) | |||||

| Subxiphoid | 92.42 | 100 | 100 | 28.57 | ||

| (+) | 61 | 0 | ||||

| (-) | 5 | 2 | ||||

| Fogging | 95.45 | 100 | 100 | 40 | ||

| (+) | 63 | 0 | ||||

| (-) | 3 | 2 | ||||

NGT=nasogastric tube; POCUS=point-of-care ultrasound; pH=gastric aspirate pH test; PPV=positive predictive value; NPV=negative predictive value

When the 68 patients underwent pH analysis, the NGT was verified to be in the stomach for 60 (88.24%) patients. In the eight patients in whom incorrect gastric placement of the NGT was inferred based on pH>5.5, six (75%) had taken proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), and tube placement in the stomach was confirmed in these patients by both ultrasonography and X-ray. In the remaining two patients, both ultrasonography and X-ray examinations were consistent with the findings that the NGT was not in the stomach. However, X-ray examination further confirmed that the tube was placed in the oesophagus just above the diaphragm and repositioned. Given the compatible results of the POCUS and X-ray tests despite negative pH findings, the authors decided to cross-tabulate the findings with POCUS/X-ray as the reference standard and the pH test as the index (Table 3). The aim of this subgroup analysis was to review the effectiveness of pH test based on its high false-negative value led to unnecessary X-ray controls.

Table 3. Cross-tabulation of the pH test as the index test and POCUS/X-ray as the reference test

| pH test | Reference test (POCUS or X-ray) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct position (n=66) | Incorrect position (n=2) | |||||

| (+) | 60 | 0 | 90.91 | 100 | 100 | 25 |

| (-) | 6 | 2 | ||||

POCUS=point-of-care ultrasound; pH=gastric aspirate pH test; PPV=positive predictive value; NPV=negative predictive value

False-negative pH findings were observed in 9.09% of 66 cases of correct tube positioning. The subgroup analysis indicated that the pH test has a sensitivity of 90.91%. The positive and negative predictive values of the pH test were 100% and 25%, respectively.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness and feasibility of POCUS in verifying correct placement of NGT in community settings. The 95.45% sensitivity of this method indicates that ultrasonography performed by trained community nurses can provide good diagnostic imaging in confirming NGT placement in community-dwelling patients. These findings are supported by those of Kim et al (2012) and Chenaitia et al (2012), which also suggested that ultrasonography is reliable in providing real-time imaging for verifying NGT placement in a setting where X-ray scans are not readily available.

Despite the encouraging results, correct NGT placement could not be visualised in the neck area in five (7.35%) patients who had excess movement due to cognitive impairment, excess neck contracture and malignancy. Studies by Luo et al (2011) and Tai et al (2016) also found that patients' mental incapacity and history of medical and surgical problems were major factors limiting the accuracy of scanning. Additionally, 98.53% of patients in the study group were classified as severely frail (CFS score≥7), physically or cognitively, and scanning could only be performed in these patients with them in the supine position. This may increase difficulty in viewing the image when the tube is lying posteriorly in the oesophagus.

When the NGT cannot be visualised in the stomach due to gas interposition, dynamic fogging in the stomach could be an effective way to strengthen the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for correct NGT placement (Chenaitia et al, 2012; Kim et al, 2012; Brun et al, 2014; Tai et al, 2016). In the present study, correct gastric placement was inferred based on fogging in only two of five patients in whom visualisation was difficult. The low success rate of viewing fogging may be due to environmental restrictions and because the patients were too frail to be propped up in bed. Instead, they were lying down with excess movement or contracture. More studies are required to explore the skills that lead to successful fogging tests.

Regarding the measurement of NGT insertion length, the findings correspond to those of other studies, which showed that the NEX method was not accurate in estimating correct internal tube length for safe insertion into the stomach (Chenaitia et al, 2012; Taylor et al, 2014). Although using a formula for predicting the length of tube insertion is more accurate (Hanson, 1979), the NEX method remains a direct and feasible method in daily practice. More studies are needed to determine the ideal method to measure the accuracy of insertion length.

The results of this study show that POCUS has a 100% specificity and PPV in verifying NGT placement, which is the same as those for the pH test. However, the use of acid-reducing medications leads to false-negative results in the pH test, which lowers its sensitivity and leads to the need for more X-ray controls (Taylor et al, 2014). The findings demonstrated that 67.6% of the patients, of which 80.9% and 8.8% used proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 antagonists, respectively, had required emergency admission for X-ray verification resulting from false-negative pH findings. In such cases, POCUS can avoid X-ray controls, as real-time dynamic imaging is not affected by acid-reducing medications.

In the study protocol, a pH cut-off of ≤5.5 indicates gastric placement, but it cannot completely rule out oesophageal placement (Boeykens et al, 2014; Ni et al, 2014). As feeding in the oesophagus will increase the risk of pulmonary aspiration, alternative techniques for tube placement confirmation are vital.

The results of the POCUS test in this study echo the findings of other studies, which show that ultrasonography improves diagnostic accuracy and reduces time to diagnosis (Chenaitia et al, 2012; Kim et al, 2012). The high positive and negative predictive values of POCUS further confirm that this imaging modality can avoid X-ray control and by used in conjunction with the pH test. When the gastric aspirate pH is >5.5 and a trained nurse is available, POCUS could be used as a first-line reference. However, training needs need to be kept in mind, because skills are needed to perform and interpret images competently, especially in a lone working environment. Thus, development of a standardised training curriculum with validation for nurses to perform POCUS in community settings is warranted.

Although this study was retrospective, its findings indicate that using POCUS during placement may be effective in quickly detecting misplacement, sooner than the pH or X-ray tests. This can reduce complications from undetected misplacement, a common cause of complications (Sparks et al, 2011).

Limitations

This study is a retrospective review of medical records in a single centre, and no sample size was calculated. While NGTs were correctly positioned in the neck in all cases, it was difficult to comment on the efficacy of neck ultrasonography because specificity could not be calculated. Further large-scale studies are needed to account for the low probability of incorrect positioning. Next, gas interposition, due to comorbidities and impaired cognition, may be considered a limitation of ultrasonography and explain the lower sensitivity of subxiphoid ultrasonography. Radiographic examination may be reserved as a second-line assessment method when tube placement cannot be visualised using POCUS. Another limitation of this community study is the chance of the NGT becoming displaced in the time between POCUS and X-ray examination. Real-time saving of the image of the tube visualised in the stomach before patients are sent for X-ray could help to weigh the evidence surrounding the effectiveness of POCUS in future studies.

Conclusions

POCUS is effective in verifying correct NGT placement and providing better management for unfit patient groups in community settings. It may be feasible to consider it as a first-line feeding tube position assessment. POCUS would not only enhance decision-making processes at the point-of-care but also improve patient outcomes. Further studies are required to explore the role of POCUS in different patient groups (those with different morbidities, such as vascular conditions, wounds and lung conditions) in community settings.

KEY POINTS

- Nasogastric tube (NGT) feeding is often required by community-dwelling adults, and their improper placement can lead to severe complications

- Tests are available to ensure correct placement of NGTs, but most are difficult to conduct in community settings; X-ray controls are commonly needed, but these involve emergency department visits

- The main reference test used, the gastric aspirate pH test, is affected by various factors, and aspirate cannot be obtained sometimes

- Point-of-care ultrasonography using handheld devices is a possible alternative test for rapid verification of NGT placement

CPD REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

- How do you verify correct placement of nasogastric tubes (NGTs) in your practice?

- What are the advantages of point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) using handheld devices for verification of NGT placement?

- How would patient outcomes improve if POCUS were used to verify accurate NGT placement?