There is much concern about work-related stress especially among NHS staff as a consequence of the heightened workload demands of the COVID-19 pandemic (UK Parliament, 2020). While there has been a focus on frontline hospital staff, community staff, including community nurses, have had to adapt their ways of working to reduce face-to-face contact, which has included greater use of technology to assess and support clients remotely, as well as managing increased workloads (Green, 2020). Additionally, some community nurses have had sole responsibility for some of those shielding, with other sources of contact having ceased with the first lockdown. This is on top of the existing gap between capacity and demand in district nursing (DN) services due to increasing patient numbers, patient acuity and the complexity of care, and the lack of a comparable increase in the workforce.

Green (2021) reported the findings of a Royal College of Nursing (RCN) District Nursing Forum survey conducted in November 2020, which revealed that DN services continue to provide care when other services are at capacity—that is, they are a safety net but without limits to their capacity. Unsurprisingly, the survey respondents described how their services had been under intense pressure, which meant that they had regularly postponed planned care to another day or referred to another service to manage lack of capacity. Only 1% of survey respondents reported being able to leave work on time every day, and 70% reported that they were unable to have a lunch break every day, highlighting the need for greater investment in DN provision. This gap between demand and capacity in DN has a negative impact on staff wellbeing (Maybin et al, 2016).

Prior to the pandemic, more than a third of NHS staff reported feeling unwell due to work-related stress, and one in five of those working in community trusts in 2017 had left their jobs (NHS Improvement (NHSI), 2019). Over an 8-week period prior to April 2020, 50% of the 996 NHS staff surveyed online reported that their mental health had declined, and 21% of health professionals reported that they were more likely to leave their profession due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Thomas and Quilter-Pinner, 2020). While acknowledging that much of the data have been collected in the hospital setting, there is clear evidence that many NHS staff have been impacted by the pandemic, with experience of stress, anxiety, trauma and bereavement, which is exacerbated by social distancing from their usual support network (Thomas and Quilter-Pinner, 2020).

Burnout

Burnout is a response to excessive stress at work, resulting in emotional exhaustion, de-personalisation and reduced personal accomplishment (see the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI); Maslach and Jackson, 1981). It occurs when there is a prolonged mismatch between a person's capacity and work demands in at least one of six work dimensions, namely, workload, control, reward, community, fairness and values. Maslach and Jackson (1981) contended that burnout had a negative impact on an individual's health and job performance. Other models view burnout as a process rather than a work-related state; the job demands-resources model (Demerouti et al, 2001) sets out an employee's wellbeing continuum of varying levels of exhaustion and disengagement from their work due to stressors, while others describe a process resulting in negative attitudes and behaviours with impaired functioning (Schaufeli et al, 2009). Dall'Ora et al's (2020) review, which included 91 studies, concluded that adverse job characteristics, such as high workload, low control, long shifts and low staffing levels, were associated with burnout in nursing as set out by Maslach and Jackson (1981).

Canadas De la Fuente et al (2015), whose sample included 175 community nurses within its 676 nurses in the Andalusian Health Services (Spain), found relatively high burnout in their sample, which probably reflected the economic difficulties and the occupational conditions of Spain. This study reported statistically significant differences in the levels of burnout related to a large number of the following variables: age, gender, marital status, having children, primary/community care and nursing role. Burnout, emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation were also found to be associated with personality-related variables, as were emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation. In their study of 222 Belgian hospital nurses, Geuens et al (2015) have also suggested that nurses with type D personality (tendency towards negative affectivity, such as worry and social inhibition such as lack of self-assurance) may be more vulnerable to burnout. Thus, many personal variables, as well as work-related variables, have been found to be associated with burnout in nurses, including those working in the community, which suggests that there are individual as well as organisational contributors to work-related stress.

Management and burnout

NHSI (2019) set out how a supportive organisation can promote psychological wellbeing through five interconnected organisational pillars: nature of work; behaviours, attitudes and beliefs; structure and processes; psychological safety; and leadership and management. This document details the importance of particular aspects of the work, including content, pace, control and environment among other aspects, which may impact work experience. Organisational climate arises from behaviours, attitudes and beliefs in the work place. The pillar of structure and processes includes the environmental, technological and managerial systems, such as human resources and people management systems. Psychological safety refers to the feelings of trust, respect and vulnerability within the team and organisation. The leadership and management pillar comprises how those with formal authority carry out their roles. NHSI (2019) noted that all five pillars are of equal importance in fostering a supportive organisation.

A critical incident interview study undertaken with 41 employees working in five NHS trusts explored how time pressure and demand had been well managed and not well managed (Lewis et al, 2010). Employees valued managers who managed workload and resources, showed individual consideration and took a participative approach with staff and sought their views. Authentic leadership has also been found to have a positive effect on work life (workload, control, rewards, community, fairness and value congruence), which, in turn, increased occupational coping self-efficacy, resulting in lower burnout and its associated poor mental health (Laschinger et al, 2015).

An important aspect of nursing is showing compassion, but burnout can reduce the capacity of nurses to deliver compassionate care due to emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation. Dev et al (2018) referred to compassion fatigue and reported a relationship between greater burnout and greater barriers to compassion. They also found that greater self-compassion predicted lower levels of burnout and barriers to compassion, because self-compassion enabled better management of personal stress through recognising what was within an individual's control in the workplace. Dev et al (2018) recommended that nurses should be trained in self-kindness to enhance their resilience. More recently, in a grounded theory study conducted in two NHS trusts involving 30 nurses from across a range of settings including the community, Andrews et al (2020) reported that nurses needed permission both from themselves and others to accept and engage in self-care and self-compassion. This emphasises the important role of nurse leaders in establishing a workplace culture which legitimises self-care and self-compassion.

Regrettably the various attempts to develop tools to help match nursing workload with nursing staff in hospitals have generated a range of tools which yield very different estimates of staff requirements and to date there is no evidence that they have resulted in more efficient or effective use of nursing staff (Griffiths et al, 2020). Similarly, Flo et al (2019) found that patient classification systems to measure nursing intensity and workload in community nursing lacked validity and reliability testing. It seems the challenge of developing a sound tool to match nursing workload with nursing staff remains, in part because the measurement of varying and changing patient needs is very complex.

It is anticipated that community nursing managers will seek to minimise the strain of heavy workloads and to provide a caring and supportive environment for their staff which encourages self-care and self-compassion. Nonetheless, it is likely that some community nurses may develop burnout, through no fault on their part, as their emotional resources are exhausted due to heavy workloads, despite the efforts of those around them and management due to the unique circumstances presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. DeFrank and Cooper (1987) argued that there are three levels of work-related stress/strain management interventions, namely, the individual, the individual/organisation interface and the organisation. The remainder of this article will focus on a potential intervention at the individual level, that is, a personal management plan, to address the symptoms of burnout and aid recovery. This does not diminish the importance of managers addressing job demands and/or job resources to reduce work-related strain stress.

Development of a personal management plan to address burnout

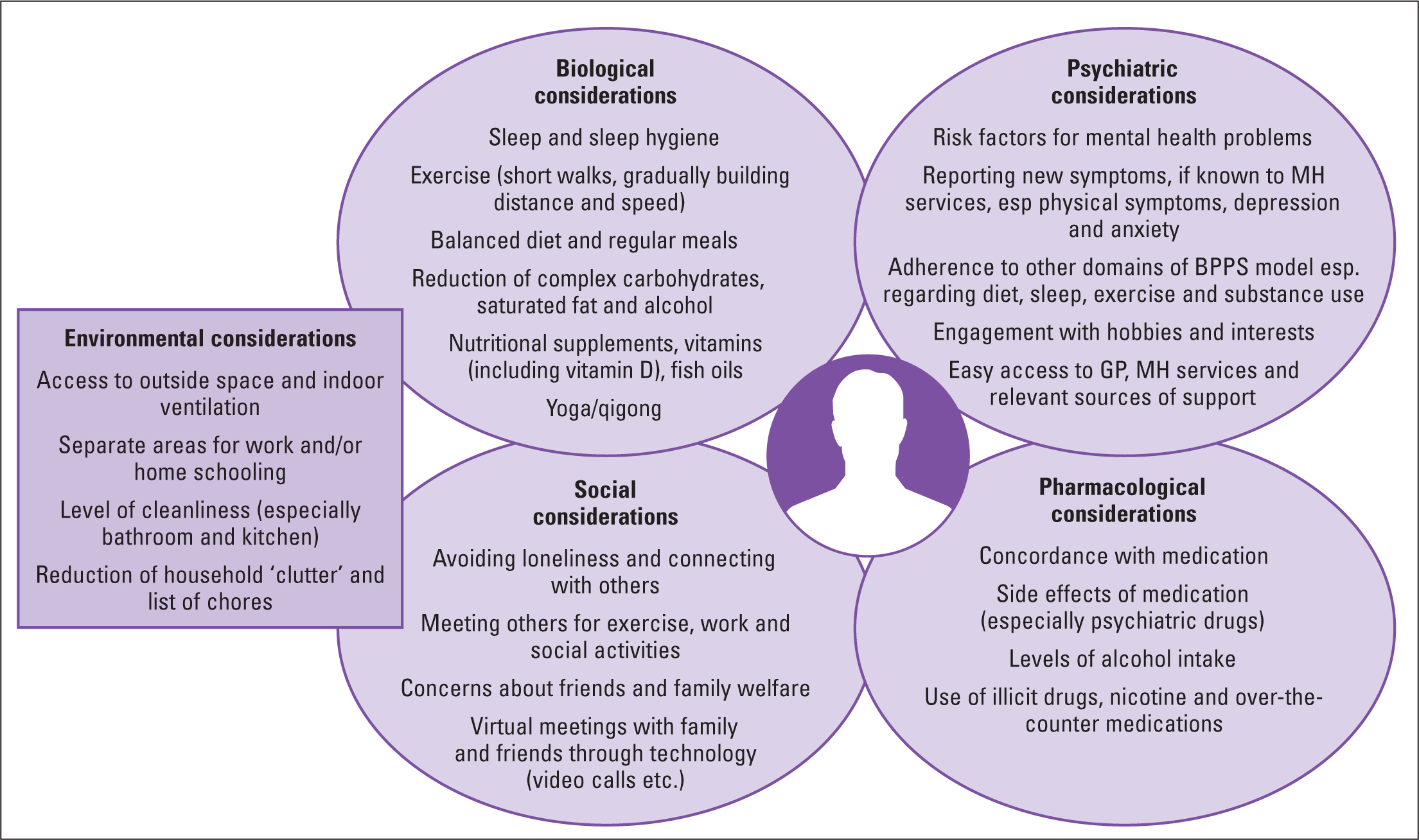

The bio-psycho-pharmaco-social model (BPPS) (Clark and Clarke, 2014) is helpful in determining how the domains of an individual and their life are inextricably linked and have an impact on each other in any given environment (McDonald and Clark, 2020a). An example of this is where an individual may overuse alcohol due to stress, which may in turn affect sleep and other biological functions and conditions. Depression and anxiety may increase, resulting in inertia, withdrawal from social contact, with further use of alcohol, and the process may become cyclical. Each individual will have their own specific map of the BPPS assessment model (Clark and Clarke, 2014). The impact of the four domains on each other in a given environment will differ from person to person. The development of a personalised map may help the individual to visualise aspects of burnout and, therefore, enable the creation of a personal management plan. Aspects of the domains may change even over a short period of time and can differ given a change in the environment (Clark and Clarke, 2014), which is especially poignant when considering periods of lockdown and imposed social isolation (Baker and Clark, 2020). Figure 1 sets out the considerations related to the BPPS domains within the given environment.

Figure 1. Example of addressing burnout utilising the bio-psycho-pharmaco-social model (Clark and Clarke, 2014)

Figure 1. Example of addressing burnout utilising the bio-psycho-pharmaco-social model (Clark and Clarke, 2014)

Biological domain

The COVID-19 pandemic will have long-term ramifications for many individuals, including those who work in the NHS and have been diagnosed with the disease (McDonald and Clark, 2020b). Stress, anxiety and depression may contribute to burnout, and there are associated biological implications. Anxiety often presents with feelings of nervousness, restlessness and/or tension, sometimes coupled with a sustained sensation of danger. Physical symptomology generally accompanies these feelings and may include tachycardia (often sustained), hyperventilation, increased perspiration, unexplained tremor, decreased concentration, poor sleep hygiene, nausea, vomiting or diarrhoea (Brandstätter et al, 2016). The sheer exhaustion associated with continued symptoms over a period of time may result in increased lethargy and the propensity for associated depression or a predisposition to a host of physical health problems.

Depression can occur over struggles to control worries and concerns, and it is often accompanied by a loss of interest in normal daily activities, lethargy, problems with memory, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, and, in extreme cases, personality changes or thoughts of self-harm, death and suicide (Bianchi et al, 2013). Notable appetite and weight changes may accompany poor sleep, and unexplained physical problems, such as headache and backache, may also be present.

Nutritional status and hydration may be affected, with weight gain or loss often being a feature of burnout. A balanced diet is recommended with regular meal times and a reduction in complex carbohydrates, saturated fats and alcohol (Eliot et al, 2018). Nutritional supplements in the form of vitamins and fish oils may be indicated in some cases, and there is a growing body of evidence that vitamin D may be helpful to the immune system, including with regard to COVID-19 (Warland, 2021).

Exercise is also of key importance in the maintenance of biological and mental health (Gerber et al, 2013), although the symptomology of stress, anxiety and depression often means that the individual feels too lethargic to follow through an exercise plan. Short walks are recommended as a starting point, gradually building in time and distance. Bischoff et al's (2019) systematic review of 18 experimental studies concluded that yoga and qigong may be an effective intervention to reduce stress among health staff.

The presence of comorbidities (especially diabetes and other endocrine disorders, cancers and cardiovascular and respiratory conditions) may complicate the overall presentation of burnout. There is an additional risk of diagnostic overshadowing with signs and symptoms of new physical health conditions not being explored further.

Psychological domain

An increased prevalence of depression, stress, anxiety, and, in some cases, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), has been identified among NHS staff who have worked through the pandemic (Tan et al, 2020). It has also contributed to fatigue and decreased performance among healthcare staff (Torales et al, 2020). Many healthcare staff have also reported increased stress and fear of infecting family members (Spoorthy et al, 2020), often complicated by the responsibility of worries over older family members and the potential of school-aged children infecting them with the disease. Depression in this instance is often referred to as an adjustment disorder, whereby the signs and symptoms are congruent with the situation to which the person has been exposed. Adjustment disorders are also common following bereavement and other stressful life events. Adjustment disorders are not always treated with antidepressant medication and, instead, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and talking therapies are often considered preferable (Raycyla et al, 2019).

For those who have a history of mental health problems, GP or community mental health services (CMHT) contact should be re-established as a matter of urgency. This is essential if the individual is experiencing thoughts of self-harm (especially suicidal ideation). Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT), generally in the form of CBT, is available via GP surgeries, but waiting lists may be longer than usual, and therapy is mainly delivered online.

Many NHS staff have experienced the loss of colleagues, family members and friends, which has contributed heavily to the feelings of stress (Torales et al, 2020). Organisations such as Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM), the Men's Health Forum, MIND, Rethink Mental Illness, SANE and the Samaritans may be useful in the healing process and in an emergency mental health situation (sources of support include Nursing Minds' mental health toolkit for nurses (https://tinyurl.com/3puxhhbb) and the Queen's Nursing Institute's (QNI) TalkToUs listening service (https://tinyurl.com/3fttz268). Many NHS organisations also have their own staff counselling services, but such services are stretched, rendering waiting times longer than usual.

The capacity for self-management of mental health problems will vary from an individual perspective, and, obviously, the severity of illness is also an important factor. Seeking early help and treatment may save unnecessary distress in the long term. Simple self-help measures for the reduction of anxiety, stress and mild to moderate depression include sleep and sleep hygiene, exercise (outdoor is preferable), diary keeping and taking time to engage with friends, family, hobbies and interests. There is overlap between biological and psychological management of care.

Pharmacological domain

The pharmacological domain of the BPPS model does not examine prescribed medication in isolation but also considers the use of alcohol, nicotine, street drugs, over-the-counter and alternative medication, all of which will have an impact on the individual and the other domains associated with health (Clark and Clarke, 2014). Concordance with prescribed medication should also be considered and, particularly, anti-depressant medication where side-effects may include sleep disturbances, lack of libido and weight gain making concordance sometimes undesirable (a change of prescription may be necessary).

Alcohol consumption is reported to have increased in some individuals during the pandemic (Kim et al, 2020). Early cross-sectional evidence has confirmed the predictions of the behavioural theories of depression and alcohol self-medication frameworks in relation to environmental reward, depression and the psychological distress with increased alcohol consumption and different coping strategies associated with the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns (McPhee et al, 2020). Although there is a lack of evidence (due to their illegal status), it is possible that the use of street drugs has also risen for similar reasons. Alcohol and street drug use should be reduced if recreational, and help sought if the situation is more serious (GP, Alcoholics Anonymous, MIND, Narcotics Anonymous).

Social domain

The impact of changes to the normal routine, including the ways that nurses work, has had an impact (McDonald and Clark 2020b) in both in-patient and community settings. Support from friends, family and colleagues is crucial, and loneliness can occur even when people do not live alone, especially when struggling with mental health issues. Talking to others is important, be it to a family member, colleague, counsellor or friend. In-person contact with family and friends outside one's household has not been permitted in the UK at certain times, although video calls may enable regular contact (through Zoom, Microsoft Teams, WhatsApp etc.) albeit in a changed format. At points during the pandemic in the UK, one could meet one other friend or family member from outside the household for a walk locally, which was important because, although social distance must be maintained, there was the added bonus of exercise and fresh air. Shopping for groceries can, in itself, provide a purpose and routine, although fear of infection may necessitate online shopping and deliveries.

Concerns about friends' and family welfare may feature highly, especially regarding older parents and relatives (Spoorthy et al, 2020). Older adults sometimes find the use of technology more problematic (Baker and Clark, 2020), so that video calls and text messages are not always possible, and telephone calls are often the media of choice and should, therefore, be encouraged.

Environmental domain

There is an association between the physical environment and mental wellbeing across a range of domains (Hext et al, 2018). The most important factors that operate independently are neighbour noise, over-crowding in the home and escape facilities such as green spaces and community gardens, and fear of crime (Guitea et al, 2006). Adequate ventilation, temperature and other occupants of the living accommodation (or no other occupants) also have an impact on mental health and wellbeing as will the imposition of lockdowns and the tier system to reduce COVID-19 transmission (Public Health England, 2020).

Levels of cleanliness (especially in the bathroom and kitchen) and the presence of clutter have also been found to have an impact on mental health and wellbeing. Place attachment and self-extension tendencies toward possessions positively contribute to psychological home, whereas clutter has a negative impact on psychological home and subjective wellbeing (Roster et al, 2016).

Childcare and home-schooling places a new challenge to working families. Those working in the NHS who have critical worker status were able to access schools and nurseries. However, some parents experienced the fear of their children being exposed to COVID-19 and the potential of bringing the virus into the home to infect more vulnerable family members. This added to the general stress of daily life, and it is helpful to instil strict hygiene procedures in the family home.

Changing what is possible to change within the imposed environment may have a positive impact on mental health and wellbeing. This can sometimes be achieved with the help of others who share the living environment, and the making of a ‘to-do’ list of chores can aid the process.

Conclusion

The workloads of many community nurses have increased alongside those of other NHS staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is likely to have impacted staff wellbeing and their mental health, in particular. Managers of community nursing services can make a difference to their staff 's wellbeing by ensuring manageable workloads and sustaining a supportive organisation which legitimises self-kindness. Managers should also recognise the particular needs of those staff with significant levels of work-related stress and burnout, and help them develop a personal management plan to aid their recovery.