The prevalence of home enteral tube feeding (HETF) is increasing (Ojo, 2015; Ford, 2019). There are various reasons why patients may require artificial tube feeding, including undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer, dysphagia relating to a cardiovascular accident or trauma and prophylactic placement for those who have a degenerative condition, such as motor neurone disease. The British Artificial Nutrition Survey (BANS) report (2018) reported that head and neck cancer was the most common reason that patients needed artificial feeding tube placements. Artificial feeding tube placement is a surgical procedure requiring significant ongoing care, maintenance and monitoring. White (2000) and Ford (2019) highlighted how patients and relatives require support around the practicalities of the feeding tube. There are common complications relating to the care of the gastrostomy site and the feeding tube, such as site infections, tube displacement and buried bumper syndrome. Patients require specialist assessment and monitoring from both a dietetic and nursing perspective.

In 2016, the role of the community nutrition nurse (CNN) was introduced at the author's service to complement the hospital-based nutrition nurse and home enteral tube feeding dietitian. This has enabled the team to adopt a proactive approach in relation to patients who are receiving HETF and may require routine or more urgent support as opposed to a reactive approach when artificial tube-related issues arise. New patients and their relatives and/or carers are counselled and offered training prior to the tube insertion procedure, and individualised care is provided in close partnership with the patient and their relatives. Troubleshooting advice is provided, with unplanned hospital attendances being the last resort rather than routine practice. The overall aim is to prevent unplanned hospital attendances and improve patients' overall experience of HETF, with individualised training, support and dedicated specialist staff.

This article describes the development and implementation of the CNN role at the author's trust, to support those receiving HETF and their carers.

Specialist care closer to home

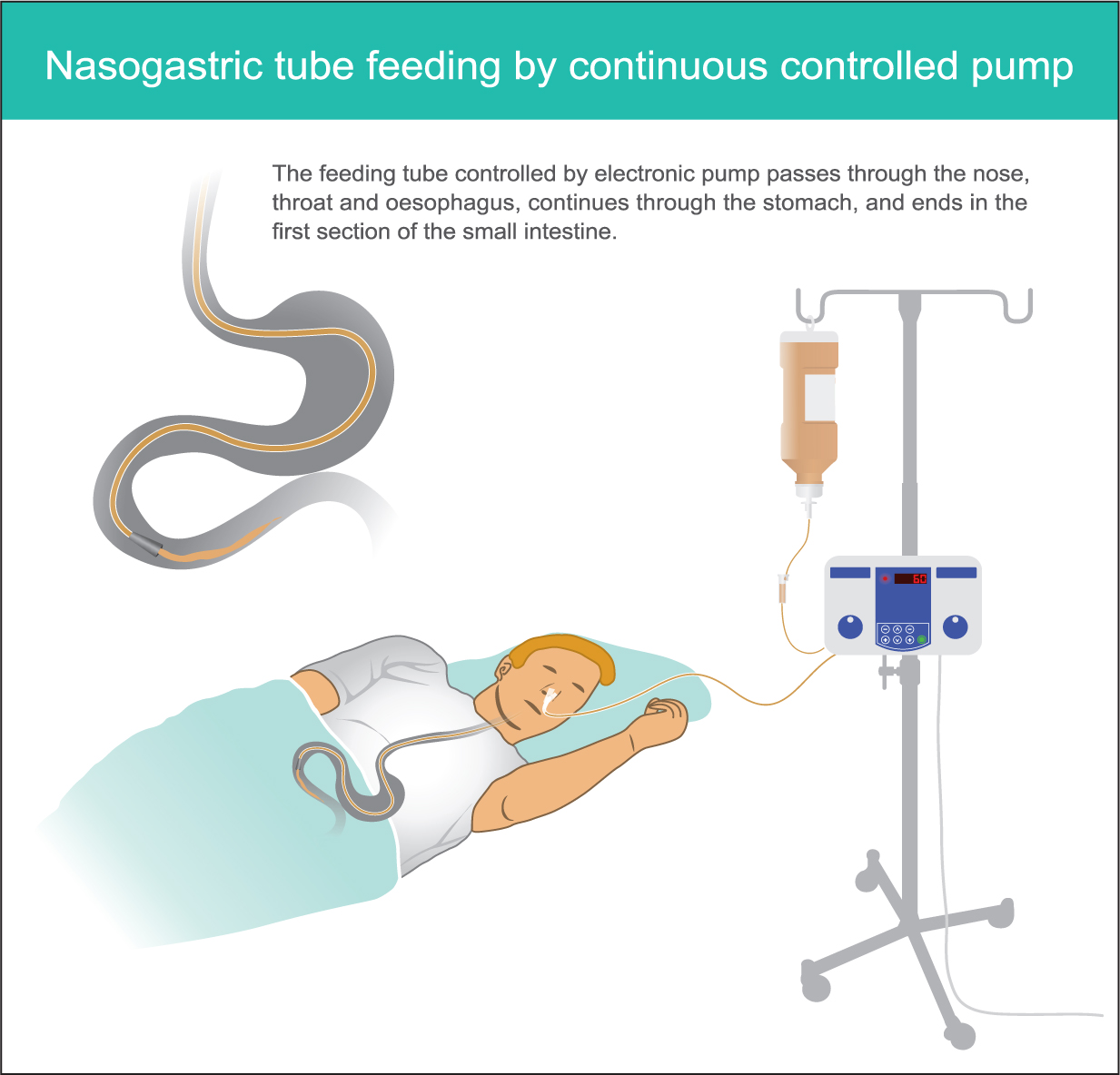

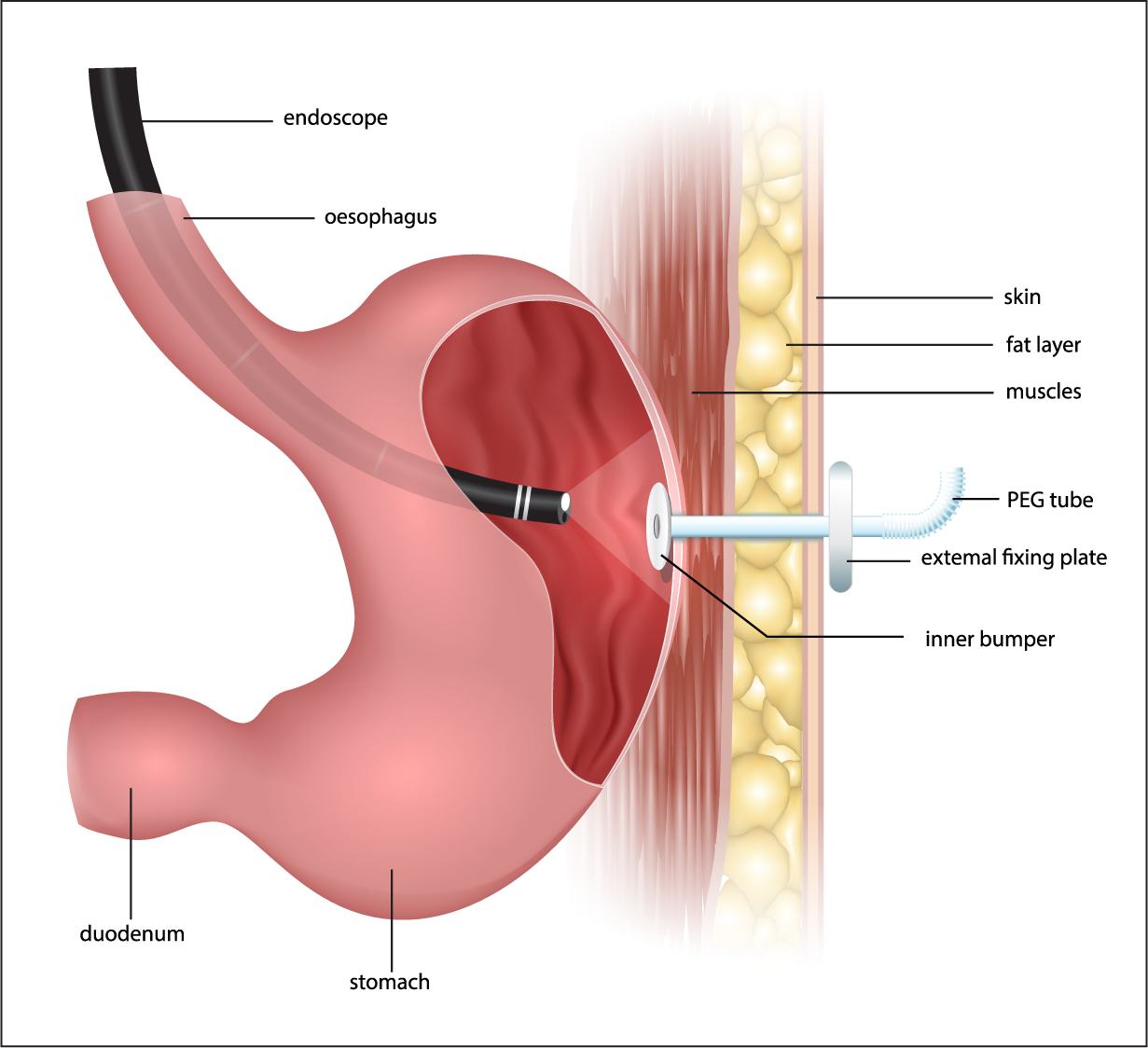

The British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (2018) described enteral tube feeding as nutrition delivered directly into a person's digestive tract through an artificial feeding tube. Artificial tube feeding is indicated where patients are unable to meet their hydration and nutritional requirements orally. Long-term artificial feeding tubes are generally inserted either endoscopically or radiologically. The initial tube insertion procedure is performed in hospital; however, the long-term care of the patient takes place in their own home or, where appropriate, a long-term care setting. It is widely acknowledged that patients have a better quality of life and there are better health outcomes when care is close to home or within the patient's own home. The NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England, 2019a) documents the ever-increasing emphasis on avoiding unplanned hospital admissions and supporting timely discharges back into the patient's home or community. Facilitating the patient's return home as soon as they are medically optimised and reducing the length of hospital stays have a positive impact on recovery and wellbeing, as well as reducing pressures on the hospital system and improving patient flow.

Across the UK, there are differences in the way patients receiving HETF are supported. Some areas have solely hospital-based nutrition nurses, and any community needs are met by a nurse attached to a nutrition company contract. Some areas have nutrition nurses based in hospitals or community clinics who also visit patients in their own home where required. This is influenced by many factors including geographical area, staffing structure and funding. In addition to nutrition nurses, dietitians also support patients receiving HETF, and, in some areas, support with feeding tube-related interventions as part of an extended role.

Prior to the development of the CNN post, the team at the author's trust consisted of a gastroenterology specialist nurse and dietitian, with a nutrition company nurse providing additional support. There was one review clinic every other week, and unplanned patient appointments for any associated enteral tube issues had to be dealt with by one of the team members in addition to other clinical commitments. Patient needs were met as required, but often as a reactive approach as opposed to a proactive one. Often, challenges were present, such as getting to hospital if a patient needed timely intervention or treatment but not necessarily requiring an emergency ambulance. Commonly, patients with long-term feeding tubes have complex needs, and accessing transport can be difficult.

First steps

With a vision to meet patients' needs in relation to enteral tube feeding closer to home and to prevent unplanned hospital admissions relating to artificial feeding tube issues, the role of CNN was developed to complement the already established team. With past experience in community nursing, care home nursing and domiciliary care, the newly appointed CNN had a good insights into the challenges that caring for patients in the community poses and the often complex comorbidities that patients and their families live with day to day.

The early stages of the work involved introductions to patients and networking with the wider multidisciplinary team, including district nurses and care homes. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2006) advocates that patients receiving HETF should have the support and care of a multidisciplinary team. Standard operating procedures were reviewed, which support the community nursing teams in their practice. The dedicated review and tube change clinic was relocated from the acute hospital to a community clinic, making it more accessible for patients. Any patients who had difficulty attending the clinic or were too unwell were seen in their own homes where possible.

Services

While HETF can provide many benefits for patients, such as meeting their nutrition and hydration requirements, there are also common complications, such as stoma site infection, over-granulation, tube displacement, damage to the tube and tube blockage. Although these complications cannot be eliminated, training and support can help to reduce the number of complications and improve patients' experience. Identifying potential issues and providing troubleshooting guidance can support patients and their carers to self-care and, therefore, access the emergency department and out-of-hours services only when necessary.

Between 2015 and 2016, prior to the introduction of the new post of CNN, there were 60 unplanned hospital attendances to the emergency department at the author's trust. At that time, specific data on the reasons for the unplanned hospital attendance and length of stay were not recorded. The average caseload for the nutrition service between 2015 and 2018 was 100 patients.

Following the implementation of the CNN role, between 2017 and 2018, the number of unplanned hospital attendances was reduced to four, corresponding to a 93% reduction (Figures 1 and 2). The reason for attendance to the emergency department included the tube becoming dislodged and tube blockage that the patient was unable to resolve themselves at home or, for those patients living in care settings, that the staff were unable to resolve. In addition to this, there were also a further three admissions to the interventional radiology or endoscopy departments for reasons such as stoma site closures and emergency percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube replacements, but these patients were admitted via the community nutrition service's virtual clinic as opposed to via the emergency department. These were interventions that could not be undertaken in either the patient's home on in a clinic environment. This meant the patients had their required procedures to resolve the issue relating to their feeding tube without delay and freed up the emergency department for other cases. If appropriate, the patients went home on the same day.

During working hours, the nutrition clinic's average response time was 45 minutes. This was a face-to-face response either in the patient's home or in a virtual clinic where patients were invited to attend the department and a suitable clinic room was located and used. Ojo (2010) identified that timely interventions can help to alleviate HETF-related complications and improve patient outcomes. Following any tube-related emergency either at the patient's home, or particularly when it results in attendance at the emergency department, the background behind the situation and the patient's individual care plan are reviewed. Any necessary follow-up, such as more training, ordering of equipment and review of policy and procedure, is carried out. Lessons are learnt from the experiences of patients, which help to shape and improve future practice.

Choosing enteral feeding

When HETF is being considered, patients are assessed and counselled for their suitability. All aspects relating to artificial tube feeding are considered, including their social circumstances, as HETF requires a significant level of ongoing care intervention by the patient and/or their relatives or carers. Patients are shown examples of the equipment required and, where possible, training is carried out prior to the artificial feeding tube insertion. Additional training and support after tube insertion are provided depending on the patient's needs, and these are agreed in partnership with the patient and their family and carers where appropriate. Ultimately, it is the patient's decision to undergo enteral tube placement. They are presented with both risks and benefits, and they are supported in their decision. Where patients lack capacity to make these decisions, these are made in best interest jointly with the multidisciplinary team and close relatives where appropriate. Patients with artificial feeding tubes are reviewed every 3–6 months, where their general wellbeing, effectiveness of the nutritional plan, routine tube changes and tube condition (depending on tube type) are assessed.

Out-of-hours plan

With the focus of the work being to prevent patients needing to attend emergency departments, patients must have a robust out-of-hours plan that they, their relatives and carers and the clinician are confident with. No two patients' out-of-hours plans are the same, and the plans will depend on a number of factors, such as their or their families' or carers' ability to manage tube-related problems and whether they are totally dependent on their feeding tube for nutrition, hydration and medication administration. One of the most common complications is feeding tube dislodgement, particularly with balloon-retained gastrostomy tubes. When this occurs, the stoma site can close over quickly, usually in 1–2 hours. To some degree, this complication is preventable, as manufacturers generally recommend checking the integrity of the water in the balloon on a weekly basis, but it does occur nonetheless. During 2017 and 2018, 14 balloon failures or balloon inflation valve failures were identified and rectified by replacing the feeding tube, which potentially prevented those tubes from displacing. These patient contacts were either undertaken in the patients' home or in clinic, thus avoiding attendance at the emergency department.

Innovations

Between 2017 and 2018, there were 25 instances of patient's tubes becoming dislodged. This is where the feeding has partially or completely come out of the stoma tract. To coincide with the introduction of the CNN post, the use of stoma plugs was also introduced at the author's service. These devices were used 12 times out of the 25 instances. A stoma plug is a simple device that can be inserted into the stoma tract should the tube become dislodged, and this prevents stoma site closure. In the case of the stoma site closing over, the patient would need to have a new tube insertion procedure. An individual risk assessment is performed to determine if the patient and or their carer is suitable and able to use the stoma plug. Written and verbal information are provided. Following the use of the stoma plug, patients are advised to telephone the service to report any problem; during out of hours, the individual care plan is followed, which is very specific to the patient. For example, if the patient is able to take some fluids orally and the HEFT service is going to be available the following morning, the patient may wait until then to prevent them having to get to the hospital. Alternatively, if they are totally dependent on their artificial feeding tube for nutrition and hydration and take regular essential medications through it, then they would need to attend the emergency department. Stoma plugs were also used four times during the 12-month period by the nutrition nurse when the stoma site had started to heal over following tube displacement. The stoma plugs come in four sizes. Most patients have a 12 Fr or 14 Fr. The smallest stoma plug is a 10 Fr, so if this size can be inserted, often with gentle rotation of the stoma plugs, they can be sized back up to the ordinal stoma size. This has prevented patients having to go through a stoma tract dilation and balloon gastrostomy tube reinsertion in interventional radiology. This not only benefits patients, but is also cost-effective.

An example of this system is given below: a patient was provided with stoma plugs to be used in the event of the balloon gastrostomy coming out. Verbal and written information were provided. The patient's balloon gastrostomy tube came out in the middle of the night. They were able insert the stoma plug and tape it in place as directed, and they contacted the CNN the next day, which was a normal working day. The patient was unable to eat and drink orally, but there were only 5–6 hours before the service was available. Thus, the patient did not need to attend the emergency department and potentially wait for several hours to be seen.

Reducing length of hospital stay

When the CNN role was developed, one of the areas of focus was reducing the length of hospital stay for patients coming into a hospital for a planned tube insertion. For patients where the decision is made to place a feeding tube, for example, following a cerebral vascular accident, this is not always possible, as patients are receiving rehabilitation and will often have lengthy stays as inpatients. Patients going into hospital for a planned, often prophylactic, tube placement can be discharged 24–48 hours post-procedure if everything goes as planned with no complications. Patients with neurodegenerative conditions such as motor neurone disease sometimes decide to have an artificial feeding tube placed, as dysphagia is a common feature of this condition. The patient is then followed up at home by the CNN the following day post-discharge. Training is carried out before the tube placement or on discharge, and changes in social circumstance, for example, the need for domiciliary care to support the use of the feeding tube, are considered prior to tube placement as part of the assessment. Local policy states that patients who have undergone a PEG placement remain in hospital for 24 hours post-procedure, and those with a radiologically inserted gastrotomy (RIG) tube placement remain in hospital for a minimum of 48 hours. Some patients and their families or carers will require more support and education than others. The amount of support and education they receive is very individual and will be ongoing. Russell (2002) discussed patients, relatives and carers training prior to discharge, highlighting that everyone's training needs are different and can depend on such things as environment, dexterity and visual acuity. The team at the author's service has found that investing that time early on and putting individual care plans in place, particularly what to do should a tube-related issue arise out of working hours, is important, as it enables patients and their families to self-care. They feel they have autonomy and some control over what happens to them and can prevent unnecessary hospital admissions and procedures. Promoting independence and, where possible, patient choice and self-care correlates with NHS's commitment to universal personalised care (NHS England, 2019b).

Multidisciplinary team working

A strength of the nutrition service is the close working relationship between the hospital and community teams. This means any patient with an artificial feeding tube who is admitted to the acute hospital is well known to the community team, who liaise with the hospital-based dietitians and nutrition nurse during the patient's admission. This, in turn, enables a smooth discharge. Patients and their carers get to know the teams and have a central point of contact. The integrated service promotes excellent communication and continuity of care. These experiences have also been related by Scott and Bowling (2015) and Brown (2019). The wider multidisciplinary team also includes speech and language therapists, Macmillan nurses, specialist palliative physiotherapist and occupational therapists to name but a few. Working together and forming strong lines of communication mean the patients benefit from a supportive team around them, information is shared to enhance patients' experience, and the care provided to patients is seamless (King's Fund, 2018).

Conclusion

With the prevalence of HETF increasing and the drive to care for people away from the acute hospital environment, the addition of a dedicated CNN, a shift to a proactive approach and using available resources to support patients when feeding tube incidents do occur have reduced the number of unplanned hospital attendances due to artificial tube-related incidents, thereby improving patient experience. While it is acknowledged that this service is not available during evenings and weekends, the volume of emergency attendances reduced significantly, whereby an out-of-hours service could not be justified. Training community nursing teams out of hours to replace dislodged tubes was also considered, but, again, with the small volume of patient numbers requiring intervention out of hours, there would be difficulty in maintaining staff competencies. Now the community nutrition service and CNN roles are established, looking to the future, the team is working towards supporting patients with nasogastric tubes in the community. This may facilitate earlier discharges and enable patients to receive HETF without delay, as nasogastric tubes can be placed at the bedside and can be used where patients do not wish to undergo the invasive gastrostomy tube procedure or are clinically not suitable to undergo the procedure.