Over the years, people have become used to the idea that bacteria colonise our skin, guts and genitalia, and recognise that changes to the microbiome cause or contribute to myriad conditions, such as atopic dermatitis, antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and bacterial vaginosis. However, fungi are often forgotten. Feet, for instance, potentially harbour almost 200 different fungal species (Casadevall and Desmon, 2024).

Worldwide, dermatophytes (ringworm) may be the most common causes of human infections, bacteria and viruses notwithstanding (White et al, 2014). It is important to adopt effective nursing approaches to manage dermatophytes, which infect skin, hair and nails, and can cause deep-tissue infections in immunosuppressed people (Dellière et al, 2024).

Introducing dermatophytes

At least 40 dermatophyte species can infect humans by ‘sticking’ to the stratum corneum, the skin's outer layer (White et al, 2014; Hill et al, 2024). Long hyphae grow into the underlying skin and break down keratin, which dermatophytes use to fuel growth (Hill et al, 2024). Between 30% and 70% of people harbour dermatophytes without experiencing any symptoms (White et al, 2014). However, some individuals experience an inflammatory response intended to eliminate the dermatophyte (Jartarkar et al, 2022; Rokas, 2022; Hill et al, 2024).

Tinea refers to the diseases caused by dermatophytes (White et al, 2014). Typically, a tinea rash is red or silver (NHS, 2023). A dermatophyte rash may seem darker than the surrounding skin. A tinea rash may be harder to see on brown and black skin as compared to white skin (NHS, 2023). The severity of the inflammation and the symptoms partly depends on how well the dermatophyte has evolved to life on human skin. Evolution optimises the relationship between host and fungi (White et al, 2014).

Anthropophilic dermatophytes, such as Trichophyton rubrum and Microsporum audouinii, prefer humans to other hosts and cause relatively mild symptoms such as itch, chronic low-level inflammation and shedding or peeling of the outer skin layers (Chanyachailert et al, 2023; Dellière et al, 2024). A study of 107 people with fungal hand infections (tinea manuum) found that scaling on the palms and itch were the most common symptoms reported by 85.9% and 75.7% of patients, respectively (Suphatsathienkul, et al 2025).

Dermatophytes can jump species barriers. Microsporum canis infects mammals as diverse as cats, dogs, gibbons, goats and guinea pigs. Meanwhile, several geophilic species grow in soil. Zoophilic (prefer animals) and geophilic dermatophytes tend to cause more severe inflammation in humans than anthropophilic fungi (Rippon, 1985; Chanyachailert et al, 2023; Dellière et al, 2024). The immune system recognises that these are ‘more foreign’ than anthropophilic dermatophytes. This means that geophilic species typically cause severe, acute disease in humans (White et al, 2014). The severity of tinea caused by zoophilic dermatophytes is somewhere between that caused by anthropophilic and geophilic species (White et al, 2014).

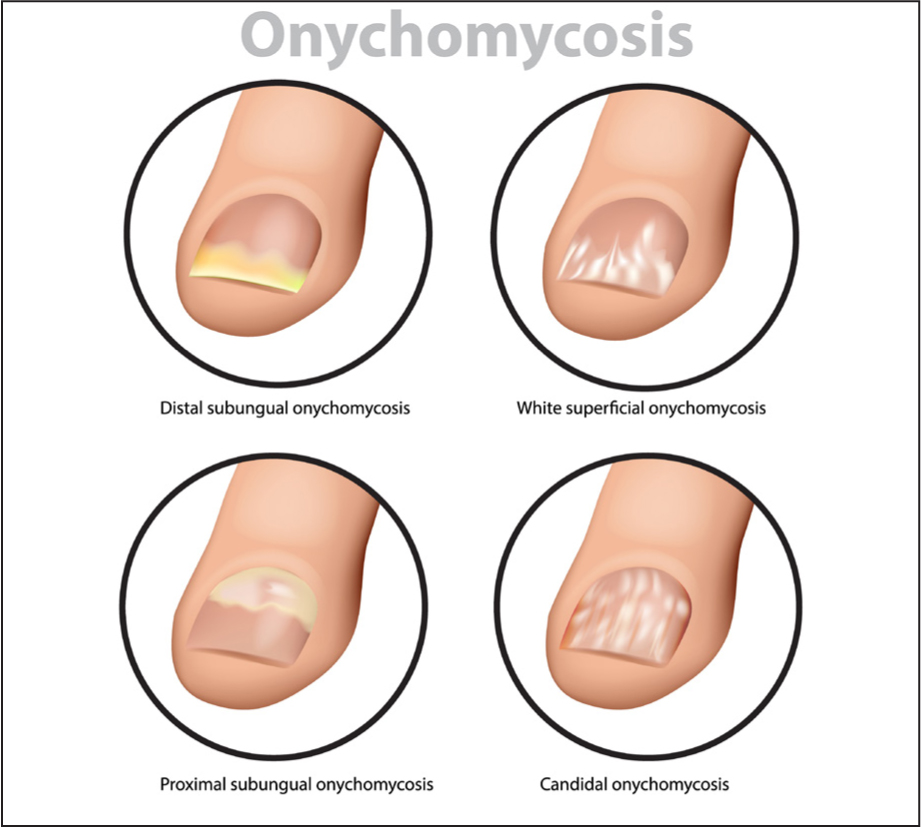

Onychomycosis of the nail

Community nurses should remain vigilant for signs of onychomycosis (fungal nail infections). Onychomycosis, the most common nail disease, accounts for approximately half of all abnormal nail cases (Kyriakou et al, 2022). Onychomycosis can cause subungual hyperkeratosis; keratinocytes accumulate under the nail plate, which may lift and detach (onycholysis) (Figure 1). Without treatment, the nail plate can thicken and crumble (Lee and Lipner, 2022). Onychomycosis may also produce ridging, ingrown nails, bleeding, nail loss and make walking painful (Gupta et al, 2020, Lee and Lipner, 2022). Buying comfortable shoes can be difficult for onychomycosis patients (Lee and Lipner, 2022). Onychomycosis may also facilitate secondary bacterial infections, which could increase the risk of foot ulcers in people with diabetes (Gupta et al, 2022).

Several diseases increase the risk of dermatophytes causing onychomycosis. For instance, knee osteoarthritis increases the likelihood of developing dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis by 14.6 times (Gupta et al, 2024). Factors that increase the risk of onychomycosis in people with knee osteoarthritis include mobility issues that hinder hygiene and patients’ ability to apply topical medicines, being older and having certain co-morbidities, such as hypertension or diabetes (Gupta et al, 2024).

Furthermore, poorly controlled diabetes can result in dysfunctional blood vessels, neuropathy and ulceration (Gupta et al, 2024). As a result, diabetes trebles the likelihood of developing toenail onychomycosis caused by dermatophytes (relative risk [RR] 2.8) (Gupta et al, 2024). Other concurrent conditions that increase the likelihood of dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis include chronic venous disease (RR 5.6), renal transplant (RR 4.7), old age (RR 4.7), being HIV positive (RR 3.7), lupus erythematosus (RR 3.1) and undergoing haemodialysis (RR 2.8) (Gupta et al, 2024).

Plaque psoriasis affects the nails in approximately half of individuals with the condition (Griffiths et al, 2021). A meta-analysis of 13 studies compared 2751 psoriasis patients with 10 967 people in the control group without the skin disease. Psoriasis patients were 68% more likely to develop onychomycosis than those in the control group (Liu et al, 2025). A psoriatic nail may lift and detach (onycholysis) from the finger or toes (which can be difficult to see in skin of colour), show orange-yellow discolouration (oil spots) or crumble (Griffiths et al, 2021; Gkini et al, 2025). Distinguishing onychomycosis from psoriasis can be difficult (Kyriakou et al, 2022); community nurses should refer to the GP if there is any doubt about the diagnosis.

There are several factors that can make psoriasis patients particularly prone to onychomycosis. For example, psoriasis can cause onycholysis, creating a moist space between the nail plate and bed that is an ideal environment for fungal growth (Kyriakou et al, 2022; Liu et al, 2025). Immune modulators used to treat psoriasis may also increase the likelihood of fungal infection (Kyriakou et al, 2022; Liu et al, 2025).

Treating tinea

Topical antifungals are generally the first-line treatment for tinea corporis (trunk, neck and limbs), tinea cruris (jock itch; groin, pubic and anogenital area) and tinea pedis (Athlete's foot) (Hill et al, 2024, Kruithoff et al, 2024). Oral antifungals may be appropriate for tinea capitis (head and scalp), onychomycosis, extensive skin infections, or if topical treatment does not resolve the infection (Hill et al, 2024; Kruithoff et al, 2024).

The choice of antifungal depends on the susceptibility of the fungus responsible, any resistance and other medications the patient is taking (check the summary of product characteristics for drug-drug and drug-diet interactions). Typically, terbinafine is particularly effective against dermatophytes (Kruithoff et al, 2024). Itraconazole and fluconazole are effective against dermatophytes, yeasts and some non-dermatophyte moulds (Gupta et al, 2020; Zaraa et al, 2024).

Perhaps inevitably, antifungal resistance is becoming more common (Sacheli and Hayette, 2021). Between 20–25% of patients with onychomycosis do not respond to antifungals and 10%–50% relapse (Zaraa et al, 2024). Community nurses should address poor adherence and other possible causes of treatment failure before assuming antifungal resistance (Kruithoff et al, 2024).

Community nurses should also ensure that patients are diagnosed and treated rapidly. For instance, pharmacists can suggest a number of treatments for dermatophytes, while GPs can prescribe more potent antifungals (NHS, 2023). Delayed or ineffective treatment can aid transmission of the fungus and encourage resistance, while antibiotics and steroids can mask or exacerbate the symptoms of a dermatophyte infection (Chanyachailert et al, 2023; Dellière et al, 2024). Tinea incognito occurs when topical or oral drugs supress the local immune system. This effectively hides the dermatophyte infection (Hill et al, 2024).

Community nurses can suggest several lifestyle changes (Table 1) that reduce the risk of antifungal failure, infection and relapse. Dermatophytes can spread from person-to-person by skin-to-skin contact during combat sports and sex (asymptomatic carriers may transmit dermatophytes), from inanimate objects (fomites) and animals or soil (Dellière et al, 2024; Kruithoff et al, 2024). Dermatophytes can also spread between parts of the body; many people with onychomycosis also have tinea pedis (Gupta et al, 2022; Dellière et al, 2024). Similarly, 43.0% and 59.8% of people with tinea manuum also have onychomycosis and fungal skin infections, respectively (Suphatsathienkul et al, 2025). Community nurses should ask whether a patient with one tinea has any outbreaks elsewhere on their bodies.

| Sanitisation and decontamination | Use ultraviolet type C light and/or antifungal sprays to decontaminate socks, shoes and other footwear. Avoid wearing old footwear |

| Change socks every day. Wear socks that ‘wick’ sweat and/or socks impregnated with copper, which is fungicidal and antibacterial | |

| Wash socks (and when possible footwear), clothes (eg gloves and socks, caps and undergarments), bedding, shower and bath mats, and towels at 60°C or hotter for at least 45 minutes | |

| Store clean and contaminated clothes away from each other | |

| Dry clothes, bedding etc well (ideally outside) and iron | |

| Wash hands after contact with soil or animals | |

| Check skin after a person has been in contact with another person or animal with ringworm | |

| Consult a vet if pets have signs of ringworm, such as patches of missing fur | |

| Lifestyle changes | Wear footwear in places where high levels of dermatophytes are likely present (eg hotel rooms, gymnasiums, communal showers, swimming pools, spas, changing rooms) |

| Wear loose-fitting clothes made of cotton and avoid sharing bed linen, towels, clothes and shoes | |

| Thoroughly dry feet and hands after showering and bathing, including the spaces between digits | |

| Consider wide-toed shoes of an absorbent material that ‘breathes’; ensure footwear fits correctly | |

| Cut nails short, keep them clean and try to avoid scratching | |

| Antifungals and over-the-counter products | Use a topical antifungal (1–3 times a week) to reduce the risk of onychomycosis recurrence |

| Older people and other patients with onychomycosis may need maintenance with topical antifungals | |

| Patients who are obese, or sweat excessively, should use absorbent powders and deodorants, change clothes frequently and lose weight | |

| Treat tinea at the first sign of relapse | |

| Caregivers and family members | Caregivers and family members should be treated if they show tinea |

| Caregivers should wash their hands frequently, especially after contact with the feet or clothing of a person with onychomycosis |

Note: Gupta et al 2020; 2022; Jartarkar et al 2022; NHS 2023; Hill et al 2024; Zaraa et al 2024

New threats

Mycologists estimate that there may be 6.2 million fungal species on Earth, although only about 150 000 have been identified (Casadevall and Desmon, 2024). To put this in context, biologists have identified about a million species of insects and approximately 6500 mammalian species (Casadevall and Desmon, 2024).

New threats can emerge from this vast reservoir of species. For instance, Bui and Katz (2024) describe Trichophyton indotineae as a dermatophyte that is, almost literally, ‘on steroids.’ T. indotineae causes extensive skin lesions and up to 75% and 25% of T. indotineae isolates are resistant to terbinafine and itraconazole, respectively (Bui and Katz, 2024; Dellière et al, 2024). T. indotineae emerged as a clinical issue in India in 2014, fuelled in part by inappropriate use of topical formulations combining high-potency corticosteroids with antifungals (Bui and Katz, 2024). Travellers and migrants can carry fungi across borders and T. indotineae has spread beyond the subcontinent and reached the UK (Bui and Katz, 2024; Casalini et al, 2024; Abdolrasouli et al, 2025).

An analysis of 157 UK cases of T. indotineae between 2017 and 2024 found that 42.7% involved the groin, buttocks and/or thighs. Another 11.5% of cases affected the abdomen, back and/or trunk. Almost all (84.7%) patients reported links to endemic areas, most commonly being of South Asian ethnicity (Abdolrasouli et al, 2025). A third (31.8%) of patients reported treatment failure: 21.7% and 4.5% showed poor responses to terbinafine and itraconazole, respectively (Abdolrasouli et al, 2025). The authors concluded that T. indotineae ‘is spreading substantially’ across the UK and, based on the current trends, predicted that T. indotineae will rapidly become the predominant cause of tinea corporis in the UK (Abdolrasouli et al, 2025).

Community nurses should not overlook fungal infections; even the seemingly benign dermatophyte can cause significant discomfort and negatively impact patients’ quality of life. Nurses should bear in mind that some fungal threats are much more insidious and serious. For instance, species of Aspergillus are found worldwide, with the exception of Antarctica. They can worsen asthma and even be deadly (Agarwal et al, 2023; Casadevall and Desmon, 2024). Mortality from invasive A. fumigatus can reach 99%, especially in immunocompromised people with advanced infections (Casadevall and Desmon, 2024). Despite being common, Casalini et al (2024) remarked:

‘Even with the numerous gaps in diagnosis and treatment, fungal infections continue to receive insufficient attention, highlighting the need for more focused research initiatives to fill these gaps.’