References

Buried bumper syndrome: prevention and management in the community

Abstract

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is a well-established form of artificial nutrition. Buried bumper syndrome (BBS) is a rare but severe complication related to this type of feeding tube. BBS is described as when the internal bumper migrates into the stoma tract and/or the mucosa, and the inner lining of the stomach starts to grow around and over the internal bumper. It can result in pain, infection and the loss of the feeding tube as a port of entry for delivery of nutrition, hydration and medication into the stomach. When suspected, BBS requires urgent referral into specialist hospital services. It is somewhat preventable with appropriate aftercare; however, incidents do occur. The evidence and guidance on care of PEGs differs, and more data and research are needed into the incidence of BBS and what influences it. Access to appropriate nutrition support teams is essential to support patients and their caregivers with all aspects of enteral feeding.

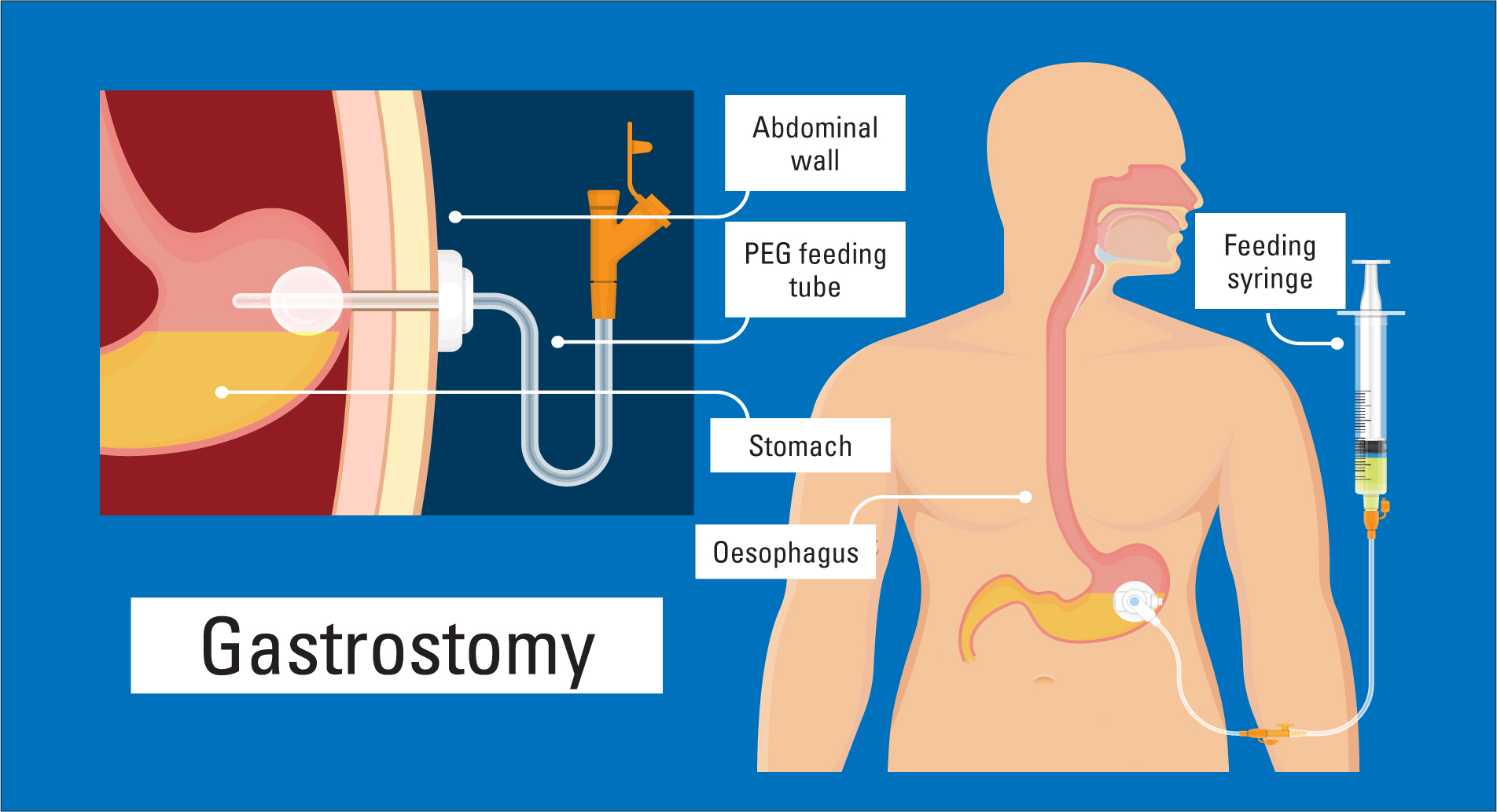

Administering artificial nutrition via a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is a well-established method for long-term enteral feeding in the UK (Figure 1). The initial PEG insertion is generally performed endoscopically and takes place in a hospital setting. The long-term care of patients is community based, either in individuals' own homes or care facilities.

Figure 1. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

Figure 1. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

Ongoing care and support of a patient with a PEG is necessary in order to prevent issues and complications. A rare but major complication of PEG is buried bumper syndrome (BBS) (Cyrany et al, 2016). PEG tubes have an internal bumper, which is generally a round disk that is positioned inside the stomach. This is the internal end of the feeding tube is where fluids, liquid artificial nutrition and medications enter the stomach. The tract which is formed during the initial endoscopic feeding tube placement is often referred to as a stoma tract. Where the PEG exits the abdomen is known as the stoma site (National Nurses Nutrition Group (NNNG), 2013).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Community Nursing and reading some of our peer-reviewed resources for district and community nurses. To read more, please register today. You’ll enjoy the following great benefits:

What's included

-

Limited access to clinical or professional articles

-

New content and clinical newsletter updates each month