Urinary incontinence is a common condition, especially prevalent among older adults, which has a profound impact on wellbeing and quality of life. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2025) defines urinary incontinence as any involuntary leakage of urine, and highlights that the main risk factor for this condition is older age, with prevalence increasing up to middle age, plateauing or decreasing between 50 and 70 years of age, and rising again with advanced age.

Urinary incontinence may occur as a result of abnormalities of the function of the lower urinary tract or of other illnesses that tend to cause leakage. However, for many, it is a consequence of the natural physiological changes that occur with ageing (NICE, 2025).

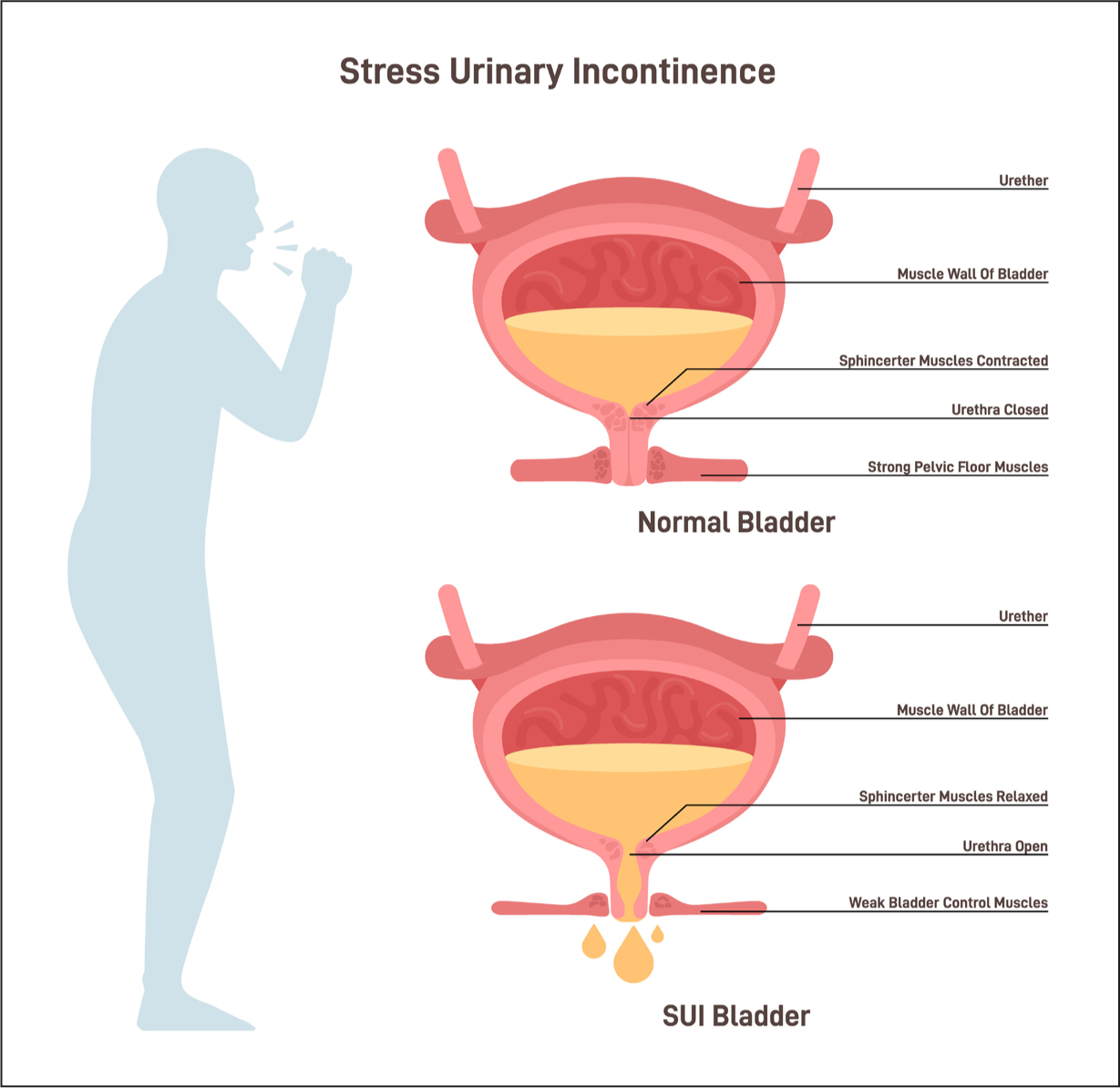

These age-related changes in the lower urinary tract include decreased bladder capacity and a feeling of fullness, decreased detrusor muscle contraction rate, decreased pelvic floor muscle strength and increased residual urine volume (Batmani et al, 2021). Damage to nerves that control the bladder from diseases such as multiple sclerosis, diabetes or Parkinson's, or conditions such as arthritis, which make it difficult to get to the bathroom in time, may also contribute to the development of urinary incontinence (National Institute on Aging, 2022).

While there are many types of urinary incontinence, those most commonly encountered in practice fall under the categories of stress, urgency and mixed urinary incontinence. Each of these categories has its own unique symptomology and treatment approach:

It is estimated that 14 million people in the UK experience some degree of urinary incontinence, with women making up the majority of this number (Lewis and Powell, 2023; NICE, 2025). Therefore, patients with urinary incontinence may struggle with its impacts and contribute significantly to the community nurse's caseload. However, systemic barriers to high-quality care provision include education for community nurses about urinary incontinence and the ways in which healthcare systems approach resourcing and management of urinary incontinence care.

The pad problem

In a systematic review concerning community nurses’ attitudes, knowledge and educational needs in relation to urinary continence, McCann et al (2022) highlighted that community nurses’ perceptions may be less favourable with regard to older people with urinary incontinence. Specific attitudes identified included the misconception that urinary incontinence becomes less distressing as people get older, with twice-hourly toileting and the use of incontinence pads as the only treatment option for older people (McCann et al, 2022).

Nurses’ attitude scores were also found to be the lowest for incontinence management when compared to three other areas of older person care, leading to nurses often using diapers and indwelling catheters to manage incontinence (McCann et al, 2022). A reliance on incontinence pads as a first-line treatment option, although contrary to best practice guidelines, is also reported across other healthcare settings, with a national audit reporting that older people received continence care that was focused mainly on the use of containment products (Kelly, 2023).

This overreliance on incontinence pads and containment products itself can cause problems: pads are sometimes not the right type or size, which can affect patient hygiene, skin integrity and dignity; 60% of urinary tract infections relate to catheter use, and almost one-third of medical and surgical inpatients are inappropriately treated with catheters (Percival et al, 2021).

Staffing and time pressures, limited continence education and the ways in which healthcare systems approach resourcing and management of urinary incontinence care are commonly cited as barriers to high-quality continence care across the literature.

Promoting holistic care

Good urinary incontinence support is holistic and empowering, encompassing multiple domains of patient care and encouraging self-management. Management of urinary incontinence in the community will mostly adhere to the conservative approach, which includes behavioural therapy (such as controlling fluid intake, prompted voiding and bladder training), pelvic floor muscle strengthening, continence aids and lifestyle changes, such as weight loss. Personalised care plans, incorporating continence aids, toileting programmes and regular monitoring and reviewing, are essential for individuals with urinary incontinence, particularly those in residential care settings (McCann et al, 2022).

Care plans must also address the physiological complications of ur inary incontinence, such as incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD), which is a common, under-recognised and painful skin condition caused by erosion of the skin from chronic exposure to urine, stool or both. The acronym ‘CPR’—cleanse, protect, restore—developed by Beeckman et al (2014), supports best practice in IAD management and outlines the steps a community nurse should take to provide care for incontinent patients.

Effectively, a cleanser with a pH close to that of the skin and containing a moisturising agent, humectant or emollient to maintain skin integrity should be applied once the skin is clean and dried. The skin should be protected with a barrier product designed to repel excess moisture that also offers protection from further damage. Barrier products are an essential part of a protective skin care regimen, ranging from creams to sprays. As with all interventions, patient assessment is key to ensure appropriateness of care, but generally barrier products such as Cocotrane cream, containing active ingredients like benzalkonium chloride and dimethicone, are a good option (Ramadan, 2024).

Psychological support must also not be neglected when it comes to urinary incontinence care. Some of the common issues related to the mental health impact of incontinence include social isolation and withdrawal; fear of falling in older adults; low mood and anxiety; and fear of intimacy and sexual activity (Robson, 2025).

There are indications that healthcare professionals can support patients in this domain by listening to their concerns; demonstrating respect, empathy and compassion, and providing continuity of care and promoting dignity (Robson, 2025). Community nurses, with their access to patients’ lived experience, are well-placed to support individuals with a condition as intimate and personal as urinary incontinence. Time, privacy, active listening and suitable training are needed to facilitate this in an effective and time-efficient manner (Robson, 2025).