Over 4.4 million people in the UK have diabetes, and over 90% of them have type 2 diabetes (Diabetes UK, 2024). The World Health Organization (WHO) (2024) defines this condition as:

‘a chronic, metabolic disease characterised by elevated levels of blood glucose, which leads over time to serious damage to the heart, blood vessels, eyes, kidneys and nerves. The most common is type 2 diabetes, usually in adults, which occurs when the body becomes resistant to insulin or does not make enough insulin. In the past three decades, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes has risen dramatically in countries of all income levels. Type 1 diabetes, once known as juvenile diabetes or insulin-dependent diabetes, is a chronic condition in which the pancreas produces little or no insulin by itself. For people living with diabetes, access to affordable treatment, including insulin, is critical to their survival. There is a globally agreed target to halt the rise in diabetes and obesity by 2025.’

In England, around 11.8 million adults are believed to be living with hypertension and 5.5 million of these are thought to have undiagnosed hypertension (Public Health England: 2017a; NCD Risk Factor Collaboration, 2021). Blood pressure is measured in millimetres of mercury (mmHg), with systolic being the highest pressure in blood vessels and diastolic being the lowest (Public Health England, 2017b). Hypertension is defined as ‘a sustained rise in blood pressure above 140/90 mmHg, and either a subsequent ambulatory blood pressure monitoring daytime average or home blood pressure monitoring average of 135/85 mmHg or higher’ (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence(NICE), 2023).

Over two-thirds of people living with diabetes also have hypertension (Ferrannini and Cushman, 2012; de Boer et al, 2017; NCD Risk Factor Collaboration, 2017). The combination of hypertension and type 2 diabetes can be fatal. The person with type 2 diabetes and hypertension has 2–4 times the risk of cardiovascular disease, end-stage kidney disease and death, compared to a normotensive and nondiabetic adult (Ferrannini and Cushman, 2012).

This article provides a concise overview of the management of type 2 diabetes and hypertension, emphasising the importance of building a collaborative partnership with the individual to support effective management. A case history approach is used to illustrate these principles in practice.

Case history

Mr Jamil Khan (name and details have been changed to protect patient confidentiality) is a 68-year-old male of south Asian ethnicity. He considered himself to be in excellent health, but began to experience minor health problems. He complained of polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, tiredness and deteriorating vision. He had been to see the optician who recommended that he should get himself checked out for diabetes. Mr Khan had the classical symptoms of diabetes. The NICE (2022) guidance recommends testing for diabetes if a person has the clinical features of diabetes, outlined in Table 1 (Nazarko, 2023).

| Symptom | Reason |

|---|---|

| Polydipsia (excessive thirst) | The body tries to reduce glucose levels by passing more urine. The person drinks more to replace lost fluid |

| Polyuria (increased urine output) | The body tries to reduce glucose levels by passing more urine |

| Polyphagia (increased appetite accompanied by weight loss) | The body is unable to use glucose effectively and the person feels hungry |

| Tiredness and irritability | The process that converts glucose into adenosine triphosphate and provides energy to the cells is affected. High blood glucose prevents the body from drawing on reserves of glycogen in the liver |

| Fungal infection | High glucose levels in blood and tissues increase infection risks |

| Poor wound healing | High glucose levels affect circulation and slow wound healing |

| Deterioration of vision | High glucose levels affect vision |

Mr Khan consented to a number of blood tests including an HbA1c blood test, which measures glycated haemoglobin. An HbA1c test measures the amount of glucose attached to the haemoglobin (known as glycation) over a 2-to 3-month period, as this is how long the blood cells typically last for in the body (MedlinePLUS, 2021). Diabetes is defined as an HbA1c greater than 48 mmol/mol (WHO, 2020).

Mr Khan's HbA1c was 120 mmol/mol. HbA1c indicates average blood glucose levels over time, and the higher the HbA1c, the greater the risk of developing diabetes-related complications. Table 2 explains how HbA1c correlates with average blood glucose levels (Diabetes.co.uk, 2023).

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | Average blood glucose (mmol/L) |

|---|---|

| 119 | 18 mmol/L |

| 108 | 17 mmol/L |

| 97 | 15 mmol/L |

| 86 | 13 mmol/L |

| 75 | 12 mmol/L |

| 64 | 10 mmol/L |

| 53 | 8 mmol/L |

| 42 | 7 mmol/L |

| 31 | 5 mmol/L |

Treatment of type 2 diabetes

Standard first line treatment of type 2 diabetes is metformin, if renal function is satisfactory (NICE, 2024). While Mr Khan's renal function was satisfactory, he did not wish to take medication and asked if there was a more natural way to manage his diabetes. Mr Khan weighed 110 kg and was 177 cm tall; his body mass index (BMI) was 37.2. He was surprised when the author pointed out that it would help to lose weight.

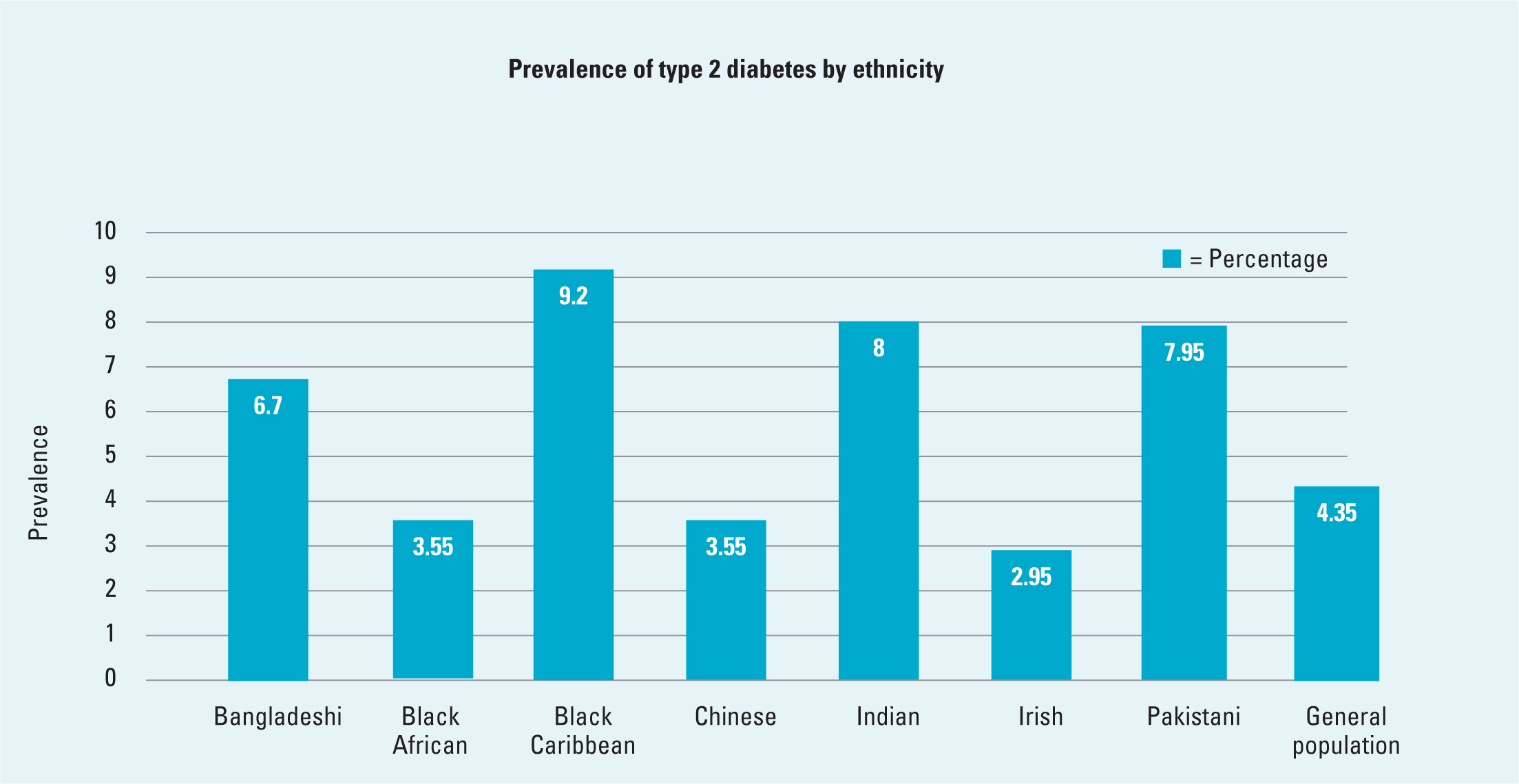

Ethnicity affects diabetes risk as well. People of south Asian and Chinese ethnicity have a lower muscle mass than white populations. As a result of this lower muscle mass and increased fat stores in people of south Asian and Chinese ethnicity, a BMI of ≥23 kg/m2 is considered overweight and BMI of ≥25 kg/m2 is considered obese. They are at a greater risk of developing diabetes than the White European population (Jenum et al, 2019). Figure 1 shows the percentage of the population who have type 2 diabetes by ethnicity. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in minority ethnic communities is alarmingly high, approximately 3–5 times higher than in the White British population (Goff, 2019). African-Caribbean ethnicities, and those from the Indian subcontinent, are at a greater risk of hypertension and complications of hypertension as compared to Caucasian people (Quan et al, 2013; van Laer et al, 2018).

Dietary control of diabetes

The author explained to Mr Khan that it would be better if he started taking medication and combined it with diet and exercise. The author explained that medication would help curb his appetite, reduce his blood glucose and make him feel better. He was adamant that he would try to lose weight and that he was not going to become one of those old men who took loads of pills.

A diabetes remission clinical trial (DiRECT) showed that 86% of people with type 2 diabetes who had been diagnosed in the last 6 years could achieve remission if they lost weight rapidly—a loss of ≥15 kg led to 86% remission, and a loss of 10–15 kg led to a 57% remission (Lean et al, 2018). A follow-up study demonstrated that these results were sustainable (Lean et al, 2024). Mr Khan agreed to see the dietician and was offered a combination of soups and shakes to help him lose weight. He declined saying that he would ‘rather chew what little food he was allowed.’ He was also given a meal plan.

Mr Khan worked very hard; he went for long walks. He lived near the hospital and the author would often see him walking in the early morning in all types of weather. He lost 25 kg in 8 months and his BMI went from 37.2 to 28.7. He was still obese and his HbA1c was 86, indicating an average blood glucose of 13 mmol. He admitted that he felt better and agreed to start metformin.

Medical treatment of diabetes

Mr. Khan agreed to start metformin at 500 mg with breakfast daily, gradually titrating to minimise gastrointestinal side effects. The dose was increased by 500 mg weekly until reaching 1 g with breakfast and dinner, or 2 g modified release once daily. As Mr Khan preferred fewer medications, the author prescribed 2 g modified release once daily.

The NICE (2024) guidelines recommend that for a person with diabetes who has been prescribed metformin, also has heart failure or cardiovascular disease, or is at risk of either, an Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor should be prescribed in addition to metformin. Metformin should be started first and the SGLT2 inhibitor should be added once the person is stabilised on metformin. SGLT2 inhibitors can be combined with insulin in people with type 2 diabetes to improve HbA1c levels and reduce body weight.

Blood pressure

Mr Khan's blood pressure was around 170/95 mm/Hg; around 40–50% of people with untreated type 2 diabetes and hypertension have a blood pressure in this range (Tidy, 2022). A blood pressure above 140/90 mm/Hg indicates hypertension.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) is normally used to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension. If ABPM is unsuitable, or the person is unable to tolerate it, home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) is used. Hypertension is classified into stages based on the readings.

If a person's blood pressure is 180/120 mmHg or higher, they need assessment for target organ damage, complications such as bleeding into the retinas, retinal haemorrhaging or swelling of the optic disk, papilloedema or any life-threatening symptoms such as new onset confusion, chest pain, signs of heart failure or acute kidney injury.

If any of these issues are present, the person will require immediate specialist assessment. Blood pressure treatment will normally be prescribed immediately, without waiting for the results of ABPM or HBPM.

If no target organ damage is identified, blood pressure measurement should be repeated within 7 days (Public Health England, 2017b; NICE, 2023). Mr Khan already had a diagnosis of stage 2 hypertension and had declined treatment in the past.

Mr Khan was not convinced that he actually had hypertension and said that the author was always finding things that were wrong with him. He agreed to monitor his blood pressure and agreed to meet with the author in 2 weeks.

When Mr Khan arrived with a list of blood pressure readings 2 weeks later, he reluctantly admitted that he was hypertensive. He asked if there was anything he could do to improve his blood pressure, other than taking pills.

Health benefits of reducing blood pressure

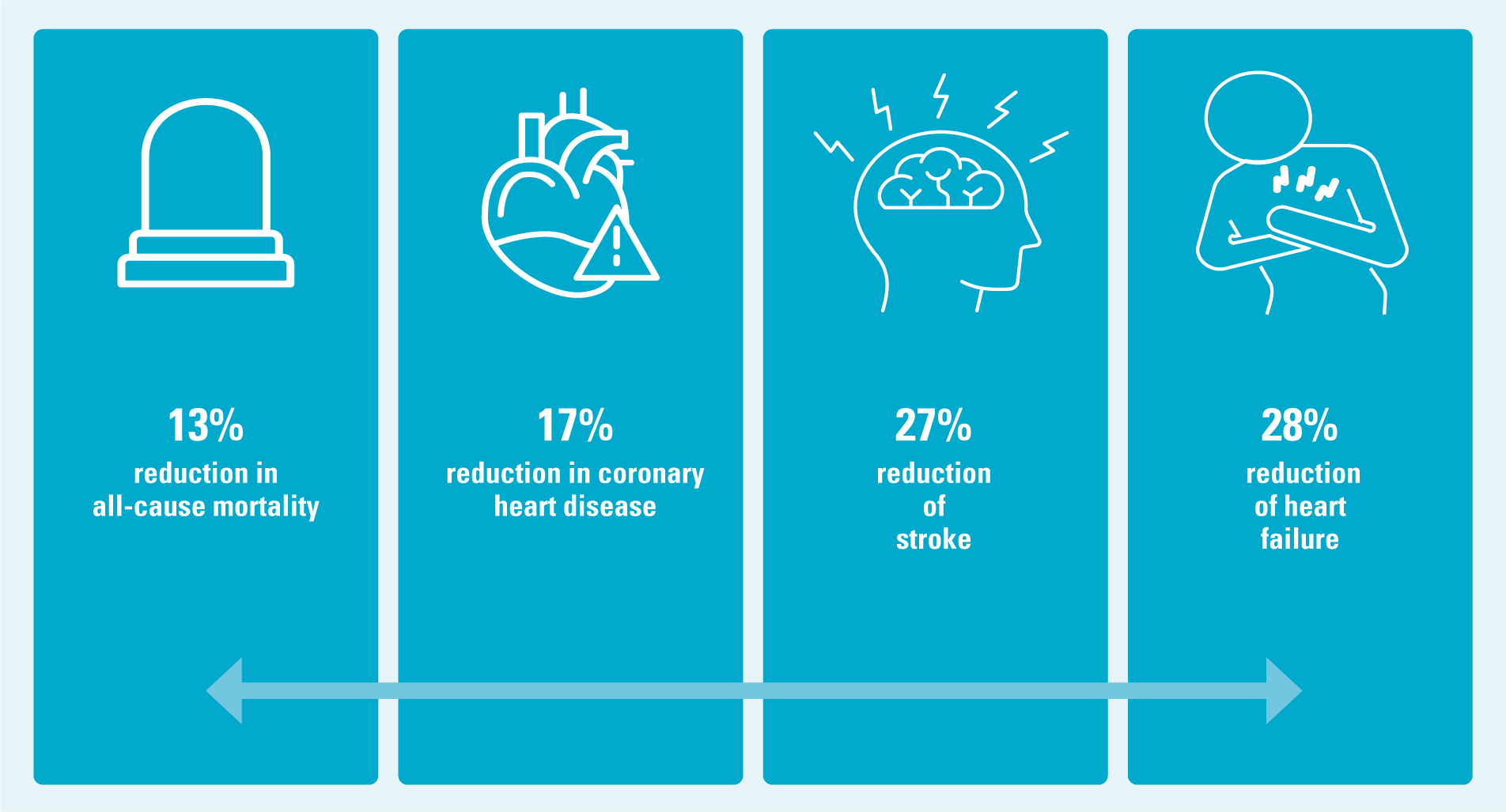

Reducing blood pressure by 10 mmHg can lead to a 13% reduction in all-cause mortality, a 17% reduction in coronary heart disease, a 27% reduction of stroke risk and a 28% reduction of heart failure (Agyemang et al, 2015) (Figure 2).

Lifestyle as medicine

While Mr Khan had been diagnosed with stage 2 hypertension, his records indicated that his blood pressure had improved because of weight loss and exercise. He now weighed 80 kg and his BMI was 27. He had lost a total of 30 kg. Stage 1 hypertension is normally treated with lifestyle changes, unless the person has significant cardiovascular risk. Losing excess weight has a huge impact on blood pressure (Ryan and Yockey, 2017).

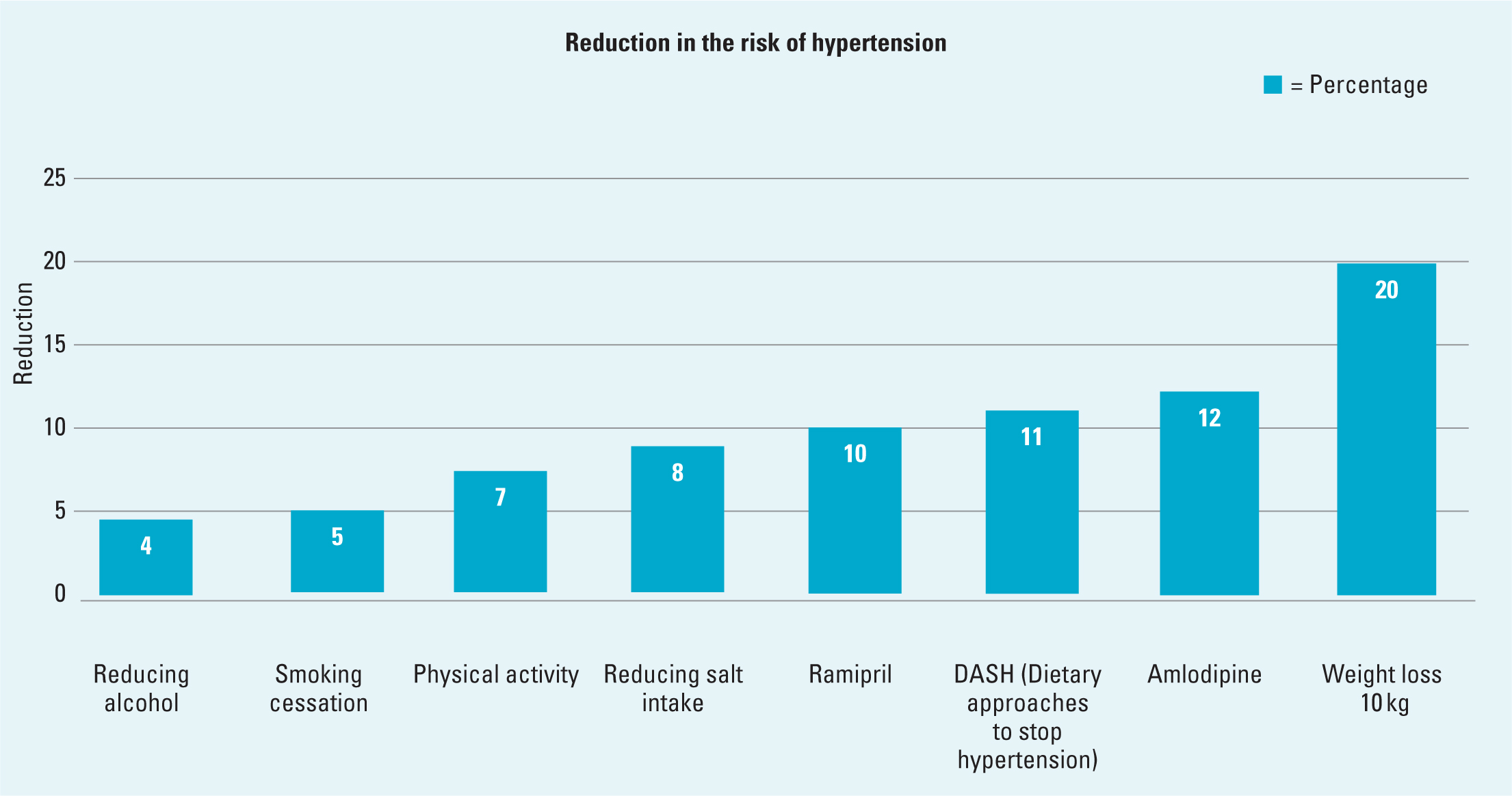

Reducing salt intake and alcohol consumption, if excessive, is helpful (NHS, 2023). It is also advisable to stop smoking as this reduces blood pressure and cardiovascular risks. Moderate intensity exercise for at least 30 minutes, at least 3 days of the week, or resistance exercise 2–3 days a week reduces blood pressure by 5–7 mmHg. This reduction in blood pressure, known as post-exercise hypotension, lasts for 24 hours following exercise and decreases coronary heart disease mortality by 9% and stroke mortality by 14% (Alpsoy, 2020). Figure 3 and Table 3 explain the effects of lifestyle changes and two commonly used medicines, ramipril and amlodipine.

| Action | Reduction in systolic BP (mmHg) | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Weight loss of 10 kg if overweight or obese | 20 | (Aucott et al, 2005; Ryan and Yockey, 2017) |

| Amlodipine (a commonly used anti-hypertensive) | 12 | (Levine et al, 2003) |

| DASH (an evidence-based eating plan high in fruit, vegetables and low-fat dairy products, with reduced salt and saturated/trans fats) | 11 | (Filippou et al, 2020) |

| Ramipril (a commonly used anti-hypertensive) | 10 | (Kaplan et al, 1993) |

| Reduce sodium intake | 8 | (Gupta et al, 2023) |

| Physical activity | 7 | (Hegde and Solomon, 2015) |

| Smoking cessation | 5 | (Gaya et al, 2024) |

| Cutting alcohol use. UK guidance advises limiting alcohol intake to 14 units per week | 4 | (Xin et al, 2001) |

Blood pressure (BP); Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)

Treatment of hypertension

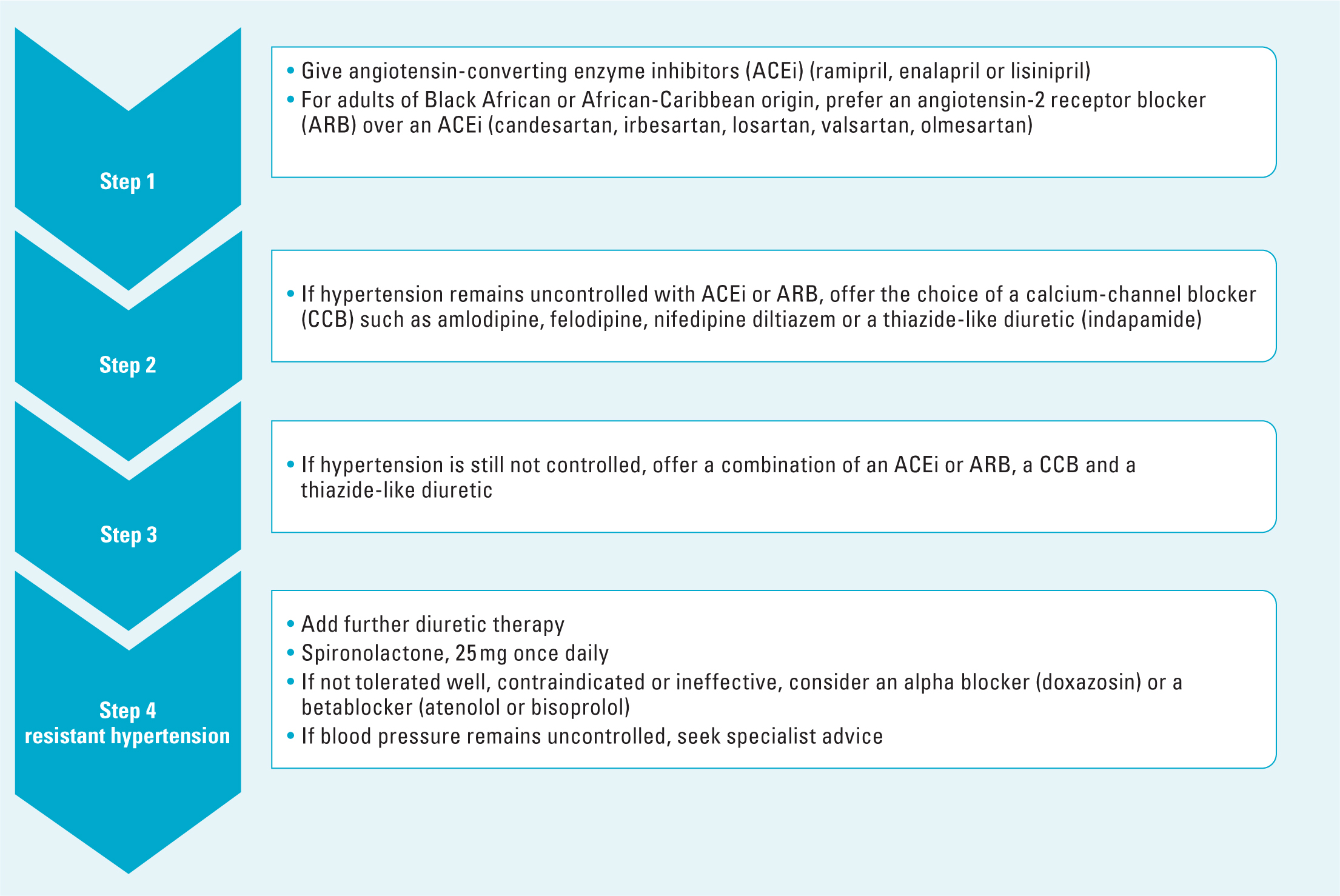

Medication may be required if the person has severe hypertension or if lifestyle changes are not effective. Treatment varies according to a person's age, ethnicity and classification of hypertension (NICE, 2023). Figure 4 and Table 4 provide details of treatment (Tidy, 2022).

| Type of anti-hypertensive | Examples | Action | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors | Enalapril, lisinopril, perindopril, ramipril | Reduce blood pressure by relaxing stiff blood vessels | The most common side effect is a persistent dry cough. Other side effects include headaches, dizziness and a rash |

| Angiotensin-2 receptor blockers (ARBs) | Candesartan, irbesartan, losartan, valsartan, olmesartan | Reduce blood pressure by relaxing stiff blood vessels. Often recommended if ACE inhibitors cause troublesome side effects. | Dizziness, headaches and cold or flu-like symptoms |

| Calcium-channel blockers | Amlodipine, felodipine, nifedipine diltiazem, verapamil | Reduce blood pressure by dilating (widening) blood vessels. | Headaches, swollen ankles and legs, constipation, urinary frequency. Grapefruit juice should be avoided |

| Diuretics | Indapamide, bendroflumethiazide | Flushing excess water and salt from the body. Used in addition to other anti-hypertensives and in heart failure | Postural hypotension; dizziness when standing up. |

| Beta blockers | Atenolol, bisoprolol | Reduce blood pressure by slowing the heart and decreasing the force of heartbeats. May be used if the person has a rapid heart beat (tachycardia) and/or hypertension | Dizziness, headaches, tiredness, cold hands and feet, vivid dreams |

Author's own work, based on NHS (2023)

Patient progress

Mr Khan did not smoke, drank moderately, was exercising gently and had adopted a healthy diet. He agreed to commence an antihypertensive. The author titrated up ramipril to 10 mg daily and this maintained his blood pressure at 130/80 mm/Hg (NICE, 2024).

Around 45% of people who are prescribed medication to treat hypertension do not take the medication as prescribed. Most people with uncontrolled hypertension (83.7%) do not take medication as prescribed. People from Asian and Afro-Caribbean backgrounds are least likely to adhere to prescribed medication regimens (Abegaz et al, 2017). People of African and Caribbean heritage are 2–3 times more likely to die of preventable heart disease and stroke than Caucasians, and one of the causes of this disparity is non-adherence to medication (Ferdinand et al, 2017).

Conclusions

Untreated or poorly managed hypertension can have a devastating effect on a person's life. It is important that the nurse works in partnership with the person to develop a relationship that supports the person with lifestyle changes, observing for adverse effects of treatment and working as part of the team to provide life enhancing care.