Over the past decade there has been a demographic shift in the UK's population, which has seen the proportion of older people rising. The United Nations estimate that, by 2050, older people over the age of 65 years will form one of the largest age groups in societies, exceeding those under 5 years and adolescents (Department for Economics and Social Affairs and United Nations, 2019). According to the Centre for Ageing Better (2023), those aged 65 years and over currently comprise 20% of England's total population, with the number of older people predicted to increase further over the next 40 years. The ageing population can be attributed to several factors including demographic changes, political influences, and social and health care trends (Scott, 2021). Improved healthcare and chronic disease management has contributed to an increase in life expectancy, while changing attitudes towards marriage and family planning has resulted in lower fertility rates (Miles, 2023). These factors, alongside a challenging economic backdrop and a change in immigration and ending of free movement for EU nationals all contribute to an ageing population (Cangiano, 2023). The trend of an ageing population will continue to rise, with those more than 80 years old growing most rapidly (Office for National Statistics, 2023). Not only will the ageing population undoubtedly have a cultural and socioeconomic impact, it will likely have implications and challenges for future healthcare provisions (Scott, 2021). As healthcare providers we must actively ensure that services are equipped to meet the needs of our future ageing population and for services to identify those that may need health and social care support.

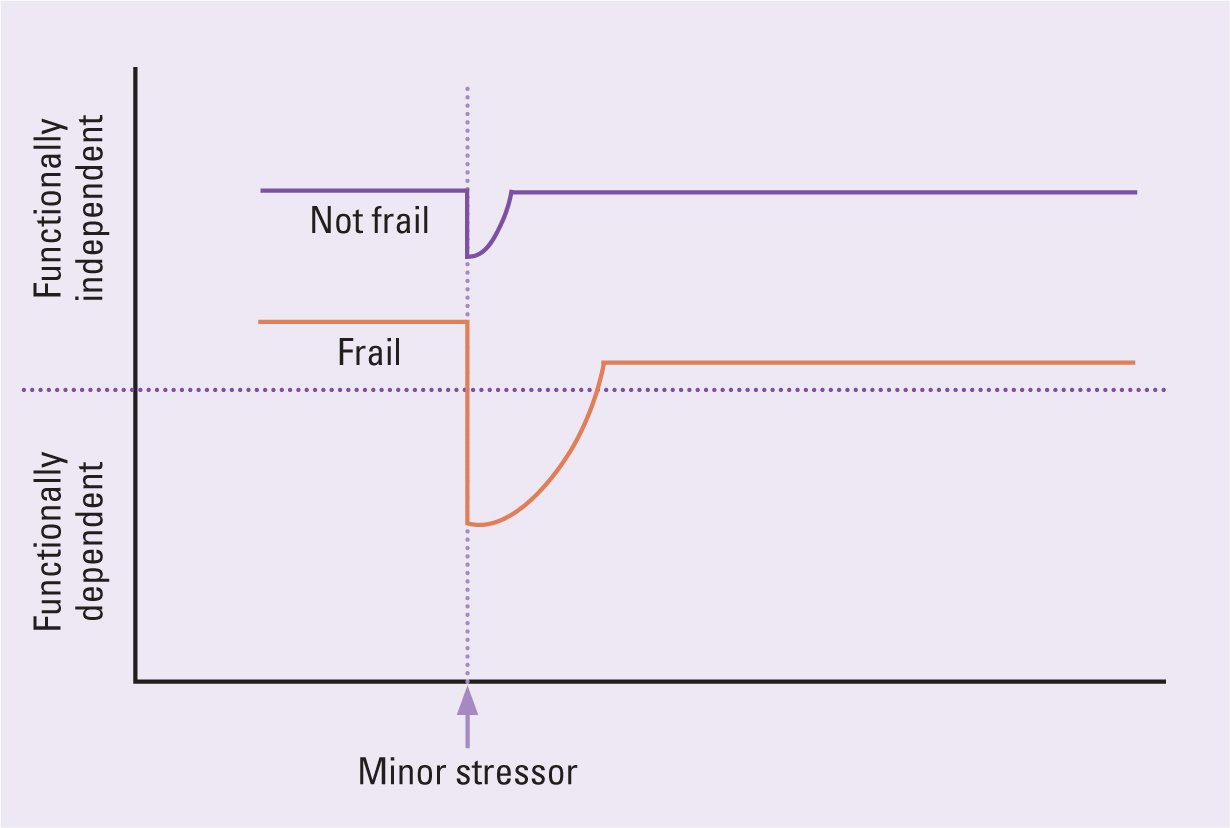

Age is not an effective way to assess the health or social care needs of an individual. For example, a 65-year-old with frailty may have higher levels of morbidity and mortality compared to a healthy 75-year-old (Rechel et al, 2020). Frailty as a syndrome has become an increasingly popular way to determine risk of adverse outcomes such as disability, morbidity and premature mortality (Dent et al, 2016). Frailty is a distinctive age-related health state, in which multiple body systems can gradually lose their reserve and resilience. A person with frailty is vulnerable to stressors (e.g. falls, minor infection, or a new drug) which leads to rapid and disproportionate decline in functional ability and loss of independence (Figure 1), which is why early identification of frailty is important (Clegg, 2015).

Identification of frailty

Early identification of frailty enables healthcare professionals to develop an appropriate care plan that is designed to meet specific needs of older people, so it is important to ask, how can we identify frailty in an individual? Arguably, any consultation between a healthcare professional and an older person presents an opportunity to identify frailty (British Geriatric Society, 2014). Frailty can lead to a person exhibiting with a seemingly straightforward presentation which masks a more complex medical problem. Broadly speaking, there are five ‘frailty syndromes’ (falls, immobility, delirium, incontinence and susceptibility to side effects of medication) and a suspicion of frailty should be considered if an older adult presents with ones of those syndromes (Kojima et al, 2018a; Baxter and Offord, 2022).

The NHS in England was the first healthcare provider in the world to proactively identify older people living with moderate and severe frailty through population-based screening, using the electronic Frailty Index (eFI) (NHS England, 2024). Developed and validated by Clegg et al (2016), the eFI uses primary care records to identify and determine patients who are at risk of frailty with robust predictive abilities for outcomes such as mortality (Kojima et al, 2018b). The tool is able to identify an older person who may be more susceptible to being admitted to hospital, a care home or requiring community health services (Clegg et al, 2016; Boyd et al, 2019). However, eFI is not a diagnostic tool; it should prompt further assessment and confirmation of frailty using a validated instrument. NICE (2016) recommends using one of the following diagnostic tests for identifying frailty in the community and primary care setting: ‘PRISMA-7’ is a brief 7 questions scale to assess frailty in older people; the ‘Gait Speed Test’ evaluates the time for a person to walk a short distance; and ‘Timed Up and Go Test’ measures the time taken for an older person to stand, walk and return to a seated position (NHS England, 2024). Although there is a range of validated instruments to measure frailty, the subjective nature of undertaking these assessments can sometimes cause differences in identification of frailty (O'Caomih et al, 2019). It has been suggested that using a two-step approach (for example, the PRISMA-7 followed by Timed Get Up and Go) would improve accuracy and help exclude some of the false positive findings when used in isolation (Watanabe et al, 2022).

Consequences of frailty

One of the most significant consequences of frailty is the impact it has on the quality of life (QoL) for not only those people living with the diagnosis, but also those who are principal carer givers. Crocker et al (2019) reviewed 22 studies, with an inclusion of over 24 000 community-dwelling people that had a mean age of 76.1 years. QoL was measured using a variety of QL instruments capturing both physical, psychological and social aspects of life. It was evident from the review, that Crocker et al (2019) found those living with frailty had a poorer QoL than those not identified as such, with limitations to activities of daily living, pain, depression, a constant focus on health and ill health and a reliance on interventions that follow for a diagnosed long-term condition.

Kojima et al (2018a) explored the consequences of frailty, particularly those in later life, with advancing frailty, recognising that a quarter of people 80 years and over are frail with multiple morbidities. The correlation between those living with conditions such as heart failure, end-stage renal disease, alzheimer disease, cancer and those living in nursing homes was significant. They further suggested that the risk of falls, fractures and subsequent disability is present with frail older people. This often results in more frequent attendance at acute hospitals, increasing healthcare costs and the development of complications associated with the condition, with some suggesting it can increase the risk of premature death (Kojima, 2018a; Stow et al, 2018).

In a study of older people's perception of the term ‘frailty’, Pan et al (2019) found that older people did not associate themselves with being frail. Older people believed that, despite requiring help with activities of daily living and being viewed as frail by healthcare professionals, the term ‘frailty’ had negative connotations. This adds another challenge for community nursing in trying to put supportive measures in place when older people may not recognise their own limitations in relation to their ageing health complexities. The authors believed that healthcare professionals were focussing on what older people could not do, rather than maintaining a focus on resilience, independence, and maximising QoL in older age in the things they could do.

Frailty and nutrition

The importance of nutrition and its role in frailty is an area of interest that researchers have been investigating for some time. It is recognised that nutrition, in its broadest concept, can have an impact upon frailty (Lochlainn et al, 2021). In a study of 2154 older participants, Hengeveld et al (2019) found that the quality of foods and lower vegetable protein food intakes were correlated with a risk of frailty in older age. Struijk et al (2020) examined the frailty risk of women over the age of 65 years. The study reviewed thousands of participant data and examined them against a criterion of people positive in more than three of the following five risk factors. A positive FRAIL scale: fatigue, reduced resistance, reduced aerobic ability, having weight loss of more than 5% between follow up appointments. A healthier, less processed diet, with lower alcohol consumption all contributed to a lower risk of frailty.

The interrelated and complex nature of our diets mean that simply focussing on visual cues to identify nutrition deficiencies and malnutrition in older people is not helpful. O'Connor et al (2023) in a study of key micronutrients in older people with frailty and cognitive problems recognises that unintentional and progressive weight loss can be a key factor in the development of frailty. Several studies support this and focus on micronutrient deficiency and its correlation to frailty, suggesting that a collection of key vitamins and mineral deficiencies can exacerbate the condition (Bartali et al, 2006; O'Halloran et al, 2020). Ng et al (2015) demonstrated that deficiency in key nutrients such as folate, vitamins B6, B12, D and calcium can contribute towards frailty and when supplementation was initiated, improvements in frailty measures were seen.

Liang et al (2021) reviewed data for 195 inpatients above the age of 65 years and measured them against anthropometric indexes, blood biochemistry results, frailty assessment and a malnutrition assessment. Comparing a frailty and a non-frailty group as defined by Fried Frailty Phenotype (Fried et al, 2001), they found malnutrition was closely linked to frailty. The anthropometric and blood biochemistry measurements were markedly lower in the frailty group and those identified as at risk in the nutritional assessment group were correlated with frailty.

Kim et al (2023) undertook a longitudinal study examining the association between nutritional status and frailty in a community dwelling for those aged 70–84 years. They found that during a 2-year follow up period, those who were identified with frailty had a correlation with moderate to severe anorexia, psychological morbidity, acute illness, and a BMI below 19. As malnutrition is strongly associated with a diagnosis of frailty, it is considered important to explore the assessment and management of nutrition as a modifiable risk factor so that this can be addressed and managed in older people (Pouyssegur et al 2015; Roy et al, 2016).

Identifying malnutrition

The State of the Nation Report (Malnutrition Task Force, 2021) estimated that over 1 million older people are either malnourished or at risk of malnutrition in the UK. The task force, which was established in 2012, works to raise awareness with both statutory, private and voluntary organisations, and provides practical guidance in addressing malnutrition and hydration in older people. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2006) helps us to define malnutrition as one or more of the risk factors seen in Box 1.

Box 1.The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence's definition of a malnourished person

- A body mass index (BMI) of less than 18.5 kg/m2

- Unintentional weight loss greater than 10% within the past 3–6 months

- A BMI of less than 20 kg/m2 and unintentional weight loss greater than 5% within the past 3–6 months

Source: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2006)

The British Association of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN) (Russel and Elia, 2014) recognised the vulnerability of older groups to malnutrition in the UK. In their most recent report identifying malnutrition as part of a national screening week, 1543 people's data were reviewed (BAPEN, 2023). The mean age of people in the study was 70 years with nearly two thirds of the cohort being over the age of 65 years. There was a variety of primary medical conditions associated with the highest prevalence of malnutrition in categories of medium to high risk as defined by the malnutrition universal screening tool (MUST) (BAPEN, 2003), of which frailty was associated with nearly half of the incidences.

The development of chronic diseases in late middle age, can often accelerate the ageing process and with it, bringing challenges in relation to nutritional status (Norman et al, 2021). Poulia et al (2012) believes that maintaining the nutritional status of older people is a complex issue, affected by what they describe as the 9 Ds: ‘dentition, dysgeusia, dysphagia, diarrhoea, depression, disease, dementia, dysfunction and drugs’. If a person experience's any of these issues, the impact on their nutritional status can be profound.

With life expectancy rising, with it comes the increased risk of living with a chronic disease, such as respiratory disorders, heart failure, stroke, dementia and cancer, to name a few (Corcoran et al, 2019). These conditions primarily affect the major systems of the body and therefore bring with them an increased risk of frequent inflammatory responses. The metabolic rate increases in the presence of disease, which can push older people towards disease-related malnutrition (DRM) because energy expenditure becomes greater than dietary intake causing a catabolic state (Cederholm, 2017). Cox et al (2020) have described the concept of ageing and malnutrition as the ‘anorexia of ageing’; the umbrella-term is widely used in describing anything from a lack of appetite in older people to those that are experiencing DRM of which frailty is recognised (Ahmed and Haboubi 2010; Wysokiński et al 2015; Cederholm et al, 2017).

In understanding the impact malnutrition plays on frailty, and the acknowledgement of its interrelated effects, the identification of the actual or potential risk of malnutrition in older people is essential. NICE (2006) recommend that screening is undertaken at every opportunity by health and social care professionals. They recommend that every patient on admission to hospital is screened and weekly thereafter, at every outpatient appointment, on admission to care homes and if there is clinical concern and on registration to a GP practice and if there are clinical concerns. NICE (2016) recommend the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) could be used to do this. Murphy et al (2018) have supported the use of the MUST tool in primary care and believe that it goes much further than just obtaining body mass index (BMI) for older people. In their retrospective review of 539 registered patients above the age of 75 years, they found that 411 had their BMI recorded and 12 patients were underweight using the BMI category. Only one patient had a MUST assessment undertaken following the low BMI (Murphy et al, 2018). In not identifying those at risk using the MUST, it was evident that further management of these patients was either missed or un-coordinated.

Managing malnutrition in older people

In identifying malnutrition in older people and particularly those with frailty, it is essential that a robust management plan is put in place (Cederholm et al, 2017). MUST supports the screening and identification of nutritional risk with recommendations for action to be undertaken according to the score calculated. While the tool has generic and advisory guidance, it forms the basis of directing the management of malnutrition with adaptation at a local level (Stratton et al, 2004).

Understanding the three categories of actual or potential risk is important to establish a personalised care plan. Stratton et al (2004) devised the tool to capture people who may display the most common issues related to malnutrition (Table 1).

Table 1. The British Association of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition malnutrition screening tool

| 0 Low Risk | 1 Medium Risk | 2 High Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Routine clinical care Repeat screening hospital – weekly care homes – monthly community – annually for special groups e.g. those >75 years | Observe

|

Treat

|

Source: Stratton et al (2004)

It is imperative that once an identified risk of malnutrition has been revealed, that actions such as collecting a dietary history is obtained. This would normally be looking back at a person's dietary habits and when a change occurred that has affected their oral intake (Norman et al, 2021). It is useful to ask the patient to start a food diary, recording their dietary intake so an assessment can be made on food consumption, requirements and deficits that may be a causal factor (Dent et al, 2023).

Food first is a common term used to treat malnutrition where oral intake remains an option for older people. Its aim is to utilise familiar likable foods, introducing smaller, more nutrient dense meal portions, perhaps more frequently (Dera and Woodham, 2016). It is at this stage that a food diary is particularly useful as it can not only record dietary consumption/portion sizes, but also triggers that may affect nutritional intake such as lack of appetite, feeling full, bloated or being nauseous (Dent et al, 2023). This can help to establish a baseline for treatment and further interventions.

Food fortification may be recommended, whereby familiar foods are fortified with extra energy and protein. For example; making hot drinks with milk rather than water, adding cream, butter and cheese to dishes and the consideration of high calorie snacks between meals (Sossen et al, 2021). While evidence of its statistical impact is questioned in many studies, due to small sample sizes and design rigour, it is thought that this intervention is still recommended as one of the first line methods to improve nutritional status in older people (Dent et al, 2023).

In addition to food fortification, oral nutritional supplements (ONS) may be recommended either over the counter products or formally prescribed by a doctor, dietitian or nurse (Taylor, 2020). The type of nutritional supplement recommended is best determined in conjunction with a healthcare professional following a robust nutritional assessment. However, it is important to understand that ONS may only provide maximum benefit when an individual is able to consume sufficient amounts of fluid orally (Dent et al, 2023). The prescribable supplements, high in nutrients and small in volume are recommended in the guidance provided by NICE (2006) and the BAPEN (2023) as part of a package of measures to address undernutrition. In a systematic review by Thomson et al (2022) in exploring the clinical and cost-effectiveness of ONS in frail older people, they failed to identify little evidence for reducing malnutrition and related negative outcomes in frail older people across a number of studies. That said, Murphy (2022) commenting directly on the results of the review, believe that larger-scale studies are required, which are robust in design and correlate ONS directly with frailty measures. Therefore, the benefits of using ONS can be seen in clinical practice.

It is important that screening, identification of nutritional risk and the subsequent planning of interventions in older people are regularly reviewed. The effectiveness of any nutritional treatment should be seen as important as any other medical intervention we provide to people (Downer et al, 2020). In the publication of the MUST screening tool, Stratton et al (2004) recommends regular evaluation as does the NICE (2006) guidelines for nutritional support in adults.

Conclusion

Frailty is a complicated syndrome of ageing which is characterised by decreased functional reserve and increased vulnerability to even minor stressors, which can have a profound impact on the health and well-being of older adults. As our population ages we must be able to identify these individuals early to mitigate those risks and provide bespoke care planning and targeted interventions.

Adequate nutrition plays an important role in physical function and as we age we become more susceptible to a change in appetite which is often a consequence of the development of emerging chronic disease associated with ageing. It is evident that the use of frailty instruments, alongside a validated nutrition risk tool can help to not only identify but support older people reverse some of the consequences of malnutrition in frailty.

Key points

- Community nursing teams will need to be prepared for the changes in the over 65 patient profile as caseloads become more complex

- The correlation between malnutrition and frailty is well documented but underreported and lacks robust management in practice

- Screening for both malnutrition and frailty in older people can help direct appropriate interventions and support community nurses in planning and executing complex care.

CPD reflective questions

- Can you easily identify the resources available to community nursing teams to aid the recognition and understanding of frailty?

- How best can you implement frailty alongside malnutrition screening in your care?

- Have you reviewed the resources available for Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool on the British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition website that support screening in the community?